by Eileen Donaldson

Knowing how stories work is almost all the battle.

~ Terry Pratchett, Witches Abroad

Introduction

While it might be a given that the actions and behaviours needed for survival would probably have been the ones humanity mastered first, it is almost certain that recounting those actions in story would have followed soon after: Nog smacks a mammoth and goes home to tell the tribe about his victorious exploits and his bravery becomes the stuff of legend, imbued with mystical and archetypal resonance the more often it is repeated. The reason for this is that the repetition, the story, serves multiple functions: it teaches others how to hunt mammoth; it amuses and lifts the heart – much back-slapping ensues; it encourages hungry, frightened folk who are threatened by the Looming Dark to believe in human ingenuity; and finally, it may perhaps become interwoven with meanings that evoke godhead, the shamanic power of the hunt and the mystical relationship between prey and hunter. Every single story ever told has these multiple levels because we are, at our very core, a story-telling species. And if we are so embedded in story – in narrating the events of our lives (“You’ll never believe what Bob did yesterday…”; “I was walking along, minding my own business, when…”; “Once upon a time…”; “It was a dark and stormy night…”) in order to make meaning of things – then it is important to stop and pay attention to the kinds of stories we tell, to the kinds of stories we believe we are living, to the stories we want to leave behind us, and to what the stories around us teach us every moment of every day. A large part of the Bardic path asks you to focus on the power of story. For the most part, this happens through the gwersu that guide you through the tale of Taliesin and Cerridwen. In these gwersu you are asked to consider the importance of each aspect of the myth including the stages of the journey and the archetypes that you meet. These are fully fleshed out so that their psychological importance can work to shift the way you understand the parts of yourself that correspond to the archetypal characters and situations, encouraging you to confront, resolve and heal the parts of yourself that the myth pinpoints for you. These archetypal characters and situations reveal something fundamental about elemental wisdom and the Wheel of the Year, about the cycles of death and rebirth that occur continually in our lives and how best to navigate them. The story of Taliesin and Cerridwen also explores truths about the processes of learning and initiation, about transformation, our potential, and the skills, wisdom and support we will gain as we walk this path. However, like all good stories, it leaves us understanding that while resolution might follow each stage of the journey, the journey itself does not end: new adventures follow every brief respite – rebirth follows death, and life demands action and engagement. And so we continually turn to new stories in order to discover secrets, tips and sketchy bits of map that might guide us through what is coming next.

A large part of the Bardic path asks you to focus on the power of story. For the most part, this happens through the gwersu that guide you through the tale of Taliesin and Cerridwen. In these gwersu you are asked to consider the importance of each aspect of the myth including the stages of the journey and the archetypes that you meet. These are fully fleshed out so that their psychological importance can work to shift the way you understand the parts of yourself that correspond to the archetypal characters and situations, encouraging you to confront, resolve and heal the parts of yourself that the myth pinpoints for you. These archetypal characters and situations reveal something fundamental about elemental wisdom and the Wheel of the Year, about the cycles of death and rebirth that occur continually in our lives and how best to navigate them. The story of Taliesin and Cerridwen also explores truths about the processes of learning and initiation, about transformation, our potential, and the skills, wisdom and support we will gain as we walk this path. However, like all good stories, it leaves us understanding that while resolution might follow each stage of the journey, the journey itself does not end: new adventures follow every brief respite – rebirth follows death, and life demands action and engagement. And so we continually turn to new stories in order to discover secrets, tips and sketchy bits of map that might guide us through what is coming next. Because of this, much has been written by various people – scholars, authors (and fans) – about the power of story and what we can learn from different kinds of narratives. But most of what they say, we already know: stories work the way they do because we respond to them instinctively – we know what they’re doing and we allow them to work their magic in us because we’ve been listening to stories every day of our lives. And it is important to acknowledge that all stories are powerful, whether they’re chapters of Dr Who, The Bold and the Beautiful, Anna Karenina, The Lord of the Rings or The Hungry Caterpillar.

Because of this, much has been written by various people – scholars, authors (and fans) – about the power of story and what we can learn from different kinds of narratives. But most of what they say, we already know: stories work the way they do because we respond to them instinctively – we know what they’re doing and we allow them to work their magic in us because we’ve been listening to stories every day of our lives. And it is important to acknowledge that all stories are powerful, whether they’re chapters of Dr Who, The Bold and the Beautiful, Anna Karenina, The Lord of the Rings or The Hungry Caterpillar.

The wonderful thing about stories is that they don’t belong to the well-read and the erudite; they belong to all of us, and although we often take them for granted or think that the only stories worth paying attention to are on the bestseller (or awards) lists, this isn’t so. Story is possibly the most powerful, omnipresent magic at work in the world and it is at work in all of our lives, all of the time. The purpose of this gwers is thus to make your intuitive understanding of story conscious so that what you have taken for granted becomes something of which you are aware, and thus something you can work with and shape. In order to do this, the first thing we need to acknowledge is that story appears in various guises in our everyday lives. Most obviously, there are the stories we listen to for edification and enjoyment – whether they’re in books, on the TV, at the cinema or in magazines. These are the tales that we’re most consciously aware of taking in because we’ve chosen to give our time to them. But stories are also woven into many other messages we receive passively every day in the form of advertisements, conversations and the narratives we tell ourselves about ourselves and the people with whom we interact. The trick here is to recognise that the same powerful process that is at work in Story, the process that teaches us about Who We Are in the Grand Scheme of Things, is also at work in these mundane narratives. We therefore need to become aware so that we choose which stories we allow to shape our spirits and our paths. It goes without saying that the narrative of ‘the happy, slim, young thing giggling into her yoghurt (on special this week)’ should probably not be allowed to shape what we think of ourselves in any meaningful way. Similarly, the tale at the water-cooler in which we paint ourselves as the righteous, misunderstood underdog might be extremely satisfying when we’ve had a bad day at work, but it is neither useful, nor healthy, to perpetuate it when shaping our destinies. And there are ‘real’ stories of which we should be wary too: we should, for example, adopt a healthy scepticism when it comes to the tales of ‘the passive princess/prince waiting for her/his prince/princess in perpetuity’ and ‘the hero who knows what’s best for everyone’. In Terry Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men, Tiffany Aching has one book to read, ‘The Goode Childe’s Booke of Faerie Tales’, and we’re told: ‘She’d never really liked the book [because] it seemed to her that it tried to tell her what to do and what to think.’ There’s an important piece of wisdom right there. Step one is becoming aware that Story is at work all around us so that in step two we actively decide what stories to listen to and which ones to disregard.

In order to do this, the first thing we need to acknowledge is that story appears in various guises in our everyday lives. Most obviously, there are the stories we listen to for edification and enjoyment – whether they’re in books, on the TV, at the cinema or in magazines. These are the tales that we’re most consciously aware of taking in because we’ve chosen to give our time to them. But stories are also woven into many other messages we receive passively every day in the form of advertisements, conversations and the narratives we tell ourselves about ourselves and the people with whom we interact. The trick here is to recognise that the same powerful process that is at work in Story, the process that teaches us about Who We Are in the Grand Scheme of Things, is also at work in these mundane narratives. We therefore need to become aware so that we choose which stories we allow to shape our spirits and our paths. It goes without saying that the narrative of ‘the happy, slim, young thing giggling into her yoghurt (on special this week)’ should probably not be allowed to shape what we think of ourselves in any meaningful way. Similarly, the tale at the water-cooler in which we paint ourselves as the righteous, misunderstood underdog might be extremely satisfying when we’ve had a bad day at work, but it is neither useful, nor healthy, to perpetuate it when shaping our destinies. And there are ‘real’ stories of which we should be wary too: we should, for example, adopt a healthy scepticism when it comes to the tales of ‘the passive princess/prince waiting for her/his prince/princess in perpetuity’ and ‘the hero who knows what’s best for everyone’. In Terry Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men, Tiffany Aching has one book to read, ‘The Goode Childe’s Booke of Faerie Tales’, and we’re told: ‘She’d never really liked the book [because] it seemed to her that it tried to tell her what to do and what to think.’ There’s an important piece of wisdom right there. Step one is becoming aware that Story is at work all around us so that in step two we actively decide what stories to listen to and which ones to disregard. Story – whether it takes the form of an epic narrative or a little moan session – is a potent tool that shapes society because it communicates the ideologies and spiritual truths of its time and it shapes each one of us in the same way. And so, as Sir Terry Pratchett suggests, ‘Knowing how stories work is almost all the battle’. We choose what stories we listen to, what stories we tell and the characters we play when we acknowledge the power of Story and the fact that we are embedded in Story from the moment we’re able to listen to and understand language.

Story – whether it takes the form of an epic narrative or a little moan session – is a potent tool that shapes society because it communicates the ideologies and spiritual truths of its time and it shapes each one of us in the same way. And so, as Sir Terry Pratchett suggests, ‘Knowing how stories work is almost all the battle’. We choose what stories we listen to, what stories we tell and the characters we play when we acknowledge the power of Story and the fact that we are embedded in Story from the moment we’re able to listen to and understand language.

How Story ‘Works’, or All Stories are the Same

There are a number of theories that attempt to explain how narrative works and why stories communicate meaning so powerfully. Some of these theories focus on genre and cultural and historical issues, others on patterns of symbol, action, character and theme. However, it could be argued that to some degree every story, regardless of genre, follows the stages of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey.

The reason for this is that conflict and the resolution of conflict are central to every story. This is true whether the story is about a gruff detective, a feisty widow on the lookout for love, a vampire-slayer, a group of children on a camp, a poor shoe-maker, a hotel manager during Christmas – or a hero undertaking a quest. On a psychological level, the basic purpose of every narrative is to help us confront our fears – that life is meaningless, that love is fragile, and that humanity is no more than the sum of its flaws. Story builds these fears into various kinds of conflict and when the protagonist, or main character, overcomes the conflict or resolves the issues, we experience a catharsis of our own. These situations may be more obviously Grand and Epic – genres like science fiction, fantasy, horror and fairy tale tend to be closer to myth in this way – or they might be less obvious and more mundane, as in genres like the realistic novel, detective fiction and romance. But the basic pattern remains the same: in each of them the protagonist has to meet the Shadow specific to his or her situation and overcome it and, vicariously, we also face our fears and resolve them, even if the resolution is temporary.

Think for a moment about the kinds of books, or movies, you most enjoy. What are the fears or issues or experiences this genre tends to explore? What sorts of genres do the people around you enjoy? It’s a curious thing that we feel a sort of guilty pleasure when we indulge in ‘popular’ genres, as though they have less weight and value than Real Literature – but what’s popular is popular for a reason: these tales meet a need in us. Children will often ask for the same story to be read again and again until they have absorbed everything they need to from it. And adults do the same, though we read the same story in different guises. This need to repeat the pattern, to confront the same fear and scratch the same itch again and again, brings us to Joseph Campbell and the psychological journey that Story encourages us to take.

Think for a moment about the kinds of books, or movies, you most enjoy. What are the fears or issues or experiences this genre tends to explore? What sorts of genres do the people around you enjoy? It’s a curious thing that we feel a sort of guilty pleasure when we indulge in ‘popular’ genres, as though they have less weight and value than Real Literature – but what’s popular is popular for a reason: these tales meet a need in us. Children will often ask for the same story to be read again and again until they have absorbed everything they need to from it. And adults do the same, though we read the same story in different guises. This need to repeat the pattern, to confront the same fear and scratch the same itch again and again, brings us to Joseph Campbell and the psychological journey that Story encourages us to take.

Myth scholar, Mircea Eliade, writes that one of the important functions of myth and ritual is that it allows people to enact ‘the eternal return’, the process of rebirth. Every so often we need to disintegrate, rest, and then come back to life renewed. This is not something that our modern society encourages on any practical level, but that need surfaces and is met in the stories we read. Even comedies and romances have moments that threaten to be tragic, moments when disintegration might occur and we sit on the edges of our chairs until the situation is resolved. But comedy is light because real disintegration is averted (Romeo gets Juliet’s letter and we all laugh about the clever con they’re pulling on their parents as they ride into the sunset). In more serious stories, however, disintegration really happens (Romeo does not receive the letter that explains Juliet’s plan, and he kills himself rather than live without the one he loves). In these tales we, the audience, die with the characters. And when we put the book down or walk out of the theatre, we are reborn because we have survived the death and are transformed by the experience, and the world around us feels more alive for it. In Myth and Reality, Eliade writes that,

In Myth and Reality, Eliade writes that,

Though in the West the tale has long since become a literature of diversion…or of escape…it still presents the structure of an infinitely serious and responsible adventure, for in the last analysis it is reducible to an initiatory scenario: again and again we find initiatory ordeals (battles with the monster, apparently insurmountable obstacles, riddles to be solved, impossible tasks, etc). [And] initiation is passing, by way of a symbolic death and resurrection, from ignorance and immaturity to the spiritual age of the adult. (1963, 201)

Effectively, what he says is that every story we listen to is an initiation into mysteries, even the ‘silly’ stories we don’t usually think about in these terms.

And so, having even a superficial understanding of the stages of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey can help you understand the process a story is asking you to undergo, and it can help you begin to see why certain kinds of stories might appeal to you. There may be real-life value in this knowledge because if you recognise that you keep returning to a certain kind of story you can pay more attention to the psychological implications and perhaps learn from it more consciously. (For example, Romances might explore the desire for hope and resolution; Horror, the need to face your darkest fears and survive; Science Fiction, the need to resolve your despair at humanity’s inhumanity; and Fantasy, the overt thrill of heroic action and the victory of ‘the good’). If you have children, it might also be interesting to note what stories they’re drawn to, how these tales reflect what they’re going through and what coping mechanisms the stories are teaching them.

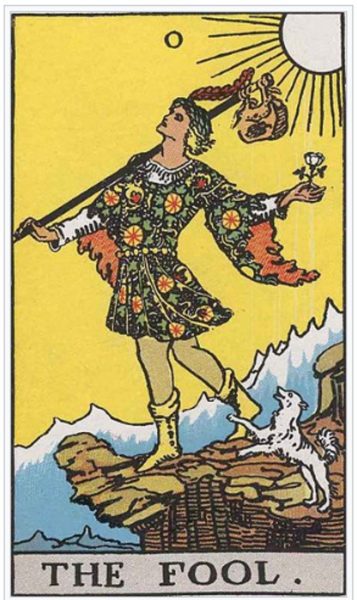

Very briefly, Campbell identifies these stages in the journey: Departure, Initiation and Return. These broad stages occur in every story but the finer steps included within each stage might not. Within the Departure falls the call to adventure, receiving supernatural aid, crossing the threshold (meeting the first obstacle and overcoming it), and the belly of the whale (a period of adjustment and learning before emerging as the hero). In the Initiation stage the hero navigates the road of trials; meets the goddess (who represents the wisdom the hero must learn) and the woman as temptress (being tempted from the heroic path); undergoes atonement with the father (meeting the God-self; becoming one with everything); apotheosis (spiritual illumination); and retrieves the ultimate boon (a gift that that the hero can take back to his or her people). In the Return the hero may refuse to go back, may require a magic flight (a quick escape) or a rescue from without, becomes the master of two worlds (having gained earthly and heavenly wisdom) and earns the freedom to live (Campbell, 1993:ix-x). In the Departure phase of the journey, it goes without saying that should the hero refuse the call to adventure, there would be no story. It is in taking up the call that the hero invites the process of change, of transformation, into his or her life. Change is magical and choosing it is an act of both courage and faith, which is why the hero receives supernatural aid. When the hero acts, the Universe responds in kind – and we know this: once committed to magic, how often don’t we come across the right books, the right teachers – thought-seeds that support us on the journey? These are akin to the old crone along the path, or the magical talking animal who gives advice to the hero as he or she begins the journey. That first threshold, however, is the first real test: will the hero give up or overcome the first trial? And the learning that happens here moves the hero into the ‘belly of the whale’, the womb in which the implications of the new role the hero has taken up become clear to him or her. When he or she accepts his or her new responsibilities, the newly birthed hero moves into the Initiation leg of the journey and steps onto the road of trials.

In the Departure phase of the journey, it goes without saying that should the hero refuse the call to adventure, there would be no story. It is in taking up the call that the hero invites the process of change, of transformation, into his or her life. Change is magical and choosing it is an act of both courage and faith, which is why the hero receives supernatural aid. When the hero acts, the Universe responds in kind – and we know this: once committed to magic, how often don’t we come across the right books, the right teachers – thought-seeds that support us on the journey? These are akin to the old crone along the path, or the magical talking animal who gives advice to the hero as he or she begins the journey. That first threshold, however, is the first real test: will the hero give up or overcome the first trial? And the learning that happens here moves the hero into the ‘belly of the whale’, the womb in which the implications of the new role the hero has taken up become clear to him or her. When he or she accepts his or her new responsibilities, the newly birthed hero moves into the Initiation leg of the journey and steps onto the road of trials.

The meeting with the goddess might take many shapes but in all of them there is a sense of wisdom being gained, and of navigating the fears associated with the mother who devours, or engaging with the love of the mother who nurtures. Consider the characters that come into the life of the hero here – those who threaten, those who nurture and those who push the hero to discover the, sometimes terrifying, truths of Being. After having made some peace with his or her place in the world, the hero encounters the woman as temptress. She need not be a woman, but Campbell uses the language of symbol here to describe whatever seduces the hero from the path. If the hero can stay the course and not be overcome by his or her desires (comfort, safety, whatever the poison of choice is) then the next step is the final trial – meeting God, which is the Self in Jungian terms. The hero sees his or her true Self reflected at him or her and that Self is the eternal soul, connected to Spirit and All-Being. In that moment the hero is transformed and becomes The Hero. And it is this recognition, this knowledge, which is the ‘boon’ the hero brings back to his or her people – to us – that we are God: that we have within us Life unbound and unsullied. This is reflected in more realistic fiction when the hero overcomes the bad guy, or the evil that’s been set up against him or her: when good triumphs, chaos is defeated, disintegration is averted and we emerge strong and victorious. The Return tends to be a fairly simple affair in most tales, unless the hero needs to escape in order to return home. The hero becomes master of two worlds because although he or she returns home, to the mundane world, he or she has been transformed by the encounter with God, with the Self. In effect, the hero has faced the threat of death and survived it and now knows his or her own strength. And we learn about our strengths vicariously through his or her actions.

The Return tends to be a fairly simple affair in most tales, unless the hero needs to escape in order to return home. The hero becomes master of two worlds because although he or she returns home, to the mundane world, he or she has been transformed by the encounter with God, with the Self. In effect, the hero has faced the threat of death and survived it and now knows his or her own strength. And we learn about our strengths vicariously through his or her actions.

It goes without saying that half the reason we read stories is that we simply cannot go adventuring for ourselves whenever we feel like it – whether this means travel to other dimensions, indulging in multiple, heady romantic dalliances, uncovering nefarious government plots or training to be ninjas; we have to be sensible (for the most part) if we enjoy the comforts of regular meals and a roof over our heads. And so we read, and go adventuring along with the characters. (And, as Dumbledore tells Harry in the final Harry Potter novel: just because it’s in your head doesn’t mean it isn’t real). As the characters navigate the stages of the hero’s journey, we do so too and we learn as they do – sometimes more than they do because the story soaks into our psyches as we read.

It is this psychological journey that makes Story so powerful because it supports us as we face our fears, as we explore our desires and as we discover more and more the richness of the human experience. The Work of the Bard

The Work of the Bard

If the work of the Bard is Story, this calls for an active engagement with this profound healing magic that is able to transform both you and the world around you. This does not mean that every Bard is going to become an author in the conventional sense, but, as a Bard, you should be aware of Story in your everyday life. Be conscious of the stories you tell in conversation because there is magic in them – you affect those listening to you and you can transform situations through the ‘spin’ you put on events. Be conscious of the stories that affect you, and the manner in which you respond to them – think about the insights to do with human experience that Story is trying to communicate to you. And be conscious of what elements of the stories around you have been manufactured – by other people and corporations – to manipulate you into playing their game, by their rules.Like any magic, Story can be used to good and bad ends and only if you are conscious of its working in your life, can you shape it to your advantage.

It is significant that Cerridwen brews the three drops of Awen to balance the ugliness of her son, Affagdu because the implication is that Awen, poetic inspiration, lifts us out of our own uglinesses – our pain, disillusionment and anger. It has this power because it reminds us that even awful events serve a purpose and that pain very often leads to inspiration and insight about the human condition. And so, although we may be in the midst of an experience and feel lost to despair and meaninglessness, Story tells us that this is so only because we cannot see the final transformative effect of what’s happening: Awen transforms human confusion and fear into faith that our lives are significant and Story teaches us that every narrative offers the gifts of wisdom, insight and, perhaps, healing. It is also important that one of the skills introduced in the Bardic Grade is that of skin-changing, explored through the transformations of Gwion and Cerridwen during the chase, because Story is all about skin-changing. Whenever you surrender to Story, you allow the experiences of the characters to become your own and in doing so, you are exposed to different lives. Story explores the choices characters make and the reasons they choose to do what they do. And in doing so, it exposes us to different worlds that exist parallel to our own and it asks us to accept that these worlds are as valid as our own and that we can learn from them. It reminds us that, by some trick of fate, we are who we are but we could be any one of the characters we meet and so we should be careful about judgement and intolerance – after all, humanity is a shared condition. As Atticus Finch teaches his children in the American classic, To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand someone until you consider things from his point of view. Until you climb into his skin and walk around in it”. Story asks us to walk around in the skins of the characters we meet, and we cannot but be transformed by the experience.

It is also important that one of the skills introduced in the Bardic Grade is that of skin-changing, explored through the transformations of Gwion and Cerridwen during the chase, because Story is all about skin-changing. Whenever you surrender to Story, you allow the experiences of the characters to become your own and in doing so, you are exposed to different lives. Story explores the choices characters make and the reasons they choose to do what they do. And in doing so, it exposes us to different worlds that exist parallel to our own and it asks us to accept that these worlds are as valid as our own and that we can learn from them. It reminds us that, by some trick of fate, we are who we are but we could be any one of the characters we meet and so we should be careful about judgement and intolerance – after all, humanity is a shared condition. As Atticus Finch teaches his children in the American classic, To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand someone until you consider things from his point of view. Until you climb into his skin and walk around in it”. Story asks us to walk around in the skins of the characters we meet, and we cannot but be transformed by the experience.

Further Reading:

Campbell, Joseph. 1993. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Fontana Press: London.

Eliade, Mircea. 2005. The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton University Press: New Jersey.

Gottschall, Jonathon. 2012. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories make us Human. First Mariner Books: New York.

Spufford, Francis. 2002. The Child that Books Built. Faber and Faber: London. Practicum

Practicum

Take a moment, with a pen and paper, and think about the genre you most enjoy to watch (as movies or TV series), or read. List five reasons why that genre appeals to you. If escapism is one of the reasons, consider what it is you’re trying to escape. There is no purpose to this exercise other than to focus on what you ‘get’ from your favourite stories. Much like any other blessing we receive, practising gratitude for the pleasure we get from Story makes us conscious of its magic in our lives. It might also be revealing to think about the genres you least enjoy and consider your reactions to them.

Next, take whatever book or movie you’ve watched most recently and try to identify the stages of the hero’s journey in the tale. Most often this will track the development of the main character. Then think about your response to each of the stages as they occurred: did you journey along with the character? What wisdom did the journey of the main character offer you?

These are both brief exercises that focus your attention on the process of Story. In the next exercise, you might want to set aside some quiet time in order to think more carefully. Although it is very difficult to identify the stages of the journey in a story that is not yet complete, you’re going to think about the stages of the hero’s journey in relation to your life. Think about the next few questions and write down whatever comes to mind.

Think about the next few questions and write down whatever comes to mind.

Are there events in your life – from childhood through to adulthood – that stand out as forcing you to grow, to face certain things, and to learn certain lessons?

Write them down and then think about the people who were involved. Who forced the process to occur, and how? Who supported your growth and if so, how? Who was just an observer/companion and what did they bring to the experience?

Then consider the outcome of each event. What did you learn? What did you have to face about yourself and life?

And finally, consider whether any of these events correspond to stages in the hero’s journey.

The last exercise of the gwers is one that you can use whenever you feel the need. In the psychological field of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy there is a strategy known as Narrative Therapy. Basically this strategy asks you to ‘tell the story’ in order to become objective about events that have upset you. For our purposes, take something that happened to you that produced a strong emotional reaction, such as an event at work that had you seething and snapping at people for days. First tell that story as though you were an outside observer and the events happened to some other unfortunate. Then retell the story as though it were comedy – again tell it as though what happened befell someone else, and concentrate on the ridiculous aspects of the situation in order to get a laugh from your listener.

This exercise encourages you to see events from a different perspective (rewriting events as comedy is particularly useful for this). And it encourages you to control what character you finally play in the narrative – victim, jester, sage. It also helps you see the overall pattern as other ‘characters’ might have experienced it. When you become the narrator, manipulating events to get a particular reaction or response from your audience, you control what that event means. This is a responsibility that most people do not consider but which the Bard should always handle carefully.

This exercise encourages you to see events from a different perspective (rewriting events as comedy is particularly useful for this). And it encourages you to control what character you finally play in the narrative – victim, jester, sage. It also helps you see the overall pattern as other ‘characters’ might have experienced it. When you become the narrator, manipulating events to get a particular reaction or response from your audience, you control what that event means. This is a responsibility that most people do not consider but which the Bard should always handle carefully.

Eisteddfod

Ulysses is one of the great heroes of Classical Mythology, often considered almost the prototype of the (civilised) trickster hero because he outsmarts so many of his enemies. Tennyson’s poem looks at an aged Ulysses and considers the restlessness and dissatisfaction of a hero who cannot give up the Quest; this excerpt is thus a reminder that we never stop journeying, that the heroic quest does not end.

From Ulysses by Alfred Lord Tennyson:

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners

Souls that have toiled, and wrought, and thought with me –

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads – you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men who strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moons round with many voices. Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles

And see the great Achilles whom we knew.

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are,

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.