These seasonal festivals can be large public events with hundreds of adults and children gathering at sacred sites, such as Stonehenge, Avebury, or Glastonbury in England, or at the other extreme, they can be very private events celebrated by a single Druid in their garden or living room, or by a small group of Druids and friends who have gathered together in a park or garden.

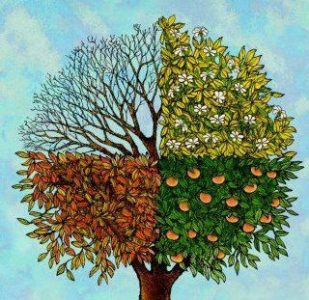

These eight seasonal festivals consist of the solstices and equinoxes – four moments during the year which are dictated by the relationship between the Earth and Sun – and the four ‘cross-quarter’ festivals which are not determined astronomically, but are related to the traditional pastoral calendar.

The summer and winter solstices are celebrated when the sun rises and sets at its most southerly point (the northern hemisphere’s midwinter) and at its most northerly point (the northern hemisphere’s midsummer). The summer solstice occurs on the longest day of the year, usually the 21st or 22nd June in the northern hemisphere and the 21st or 22nd December in the southern. The winter solstice occurs on the shortest day of the year, usually the 21st or 22nd December in the northern hemisphere and the 21st or 22nd June in the southern. The equinoxes occur when day and night are equal. The spring equinox usually occurs on the 21st or 22nd March in the northern hemisphere and the 21st or 22nd September in the southern. The autumn equinox usually occurs on the 21st or 22nd September in the northern hemisphere and the 21st or 22nd March in the southern.

The other four festivals are also related to the seasons, but are not tied to specific astronomical events. Instead they have evolved from traditional festival times linked to farming practices begun in western Europe thousands of years ago: lambing in early February, bringing the cattle out to pasture in early May, the start of the harvest at the beginning of August, and the preparations for winter at the end of October.

Druids observe this eightfold cycle of festivals by meeting together, or celebrating on their own. Sometimes the celebration will be informal – a picnic with friends, or a party during which someone will speak about the time of year and its significance, with perhaps storytelling, music or poetry. At other times the celebration will be formal. When the Order of Bards Ovates and Druids celebrates the summer solstice at Stonehenge, for example, we are all robed and enact a formal ceremony amongst the stones. But when we are on Glastonbury Tor, we try to combine a formal ritual with informal elements: several hundred adults and children, and often a few dogs, will gather together in a circle. Some people will be wearing robes of different colour and design, others will be dressed in everyday clothes. A circle will be cast by children scattering petals or blowing bubbles, and a fire eater will bless the circle with fire, while the circle is also blessed by someone sprinkling everyone with water from Chalice Well. The ritual itself is formal, in the sense that it has been prepared in advance and includes traditional elements, but the ambience is informal and joyful. Every so often all participants will cheer ‘Hurrah!’, will laugh or clap, and at the closing of the ceremony the crowd will gather in clusters to sit and chat, to admire the view, or to picnic together.

Similarly, when celebrating the festivals with a grove of Druids in Wellington, New Zealand, twenty or thirty of us, colourfully dressed, gather in a garden and celebrate the festival while honouring the Druid heritage and respecting the indigenous Maori festival time too. Visiting Maori elders are welcomed, we tell stories, recite poetry, and sing and dance together.

Often these Druid festivals include a central section called by the Welsh word ‘Eisteddfod’ which means literally ‘a festival of sitting’, but which is really a time for the expression of creativity by anyone in the circle. Although certain participants may guide the festival, and have various roles within it (such as casting or blessing the circle) no-one is acting as a priest or priestess, in the sense of being an intermediary between the other participants and Deity.

The purpose of celebrating the eight seasonal festivals is to create a pattern or rhythm in our year that allows for a few hours’ pause every six weeks or so in our busy and often stressful routine, so that we can open to the magic of being alive on this earth at this special time. It gives us a chance to fully enter the moment, to connect with the life of the earth and the land around us, and to feel the influence of the season in our bodies, hearts and minds. If we celebrate on our own, it is a time when we can enter into meditation, perhaps reviewing our life since the last festival, thinking forward to the next one, then returning to open ourselves fully to the Here and Now – soaking in the energies of earth and sky, and the trees and plants around us, and radiating our love and blessings to the Earth and all beings.

Adapted from What Do Druids Believe? by Philip Carr-Gomm, Granta, 2006

DISCOVER MORE

Learn more about Druidry and how to join the order

The practice of Druidry used to be confined to those who could learn from a Druid in person. But now you can take an experience-based course wherever you live, and when you enrol on this course, you join the Order of Bards, Ovates & Druids, and begin an adventure that thousands of people all over the world have taken. It works with the ideas and practices of Druidry in a thoroughly practical, yet also deeply spiritual way.