by Akkadia Ford

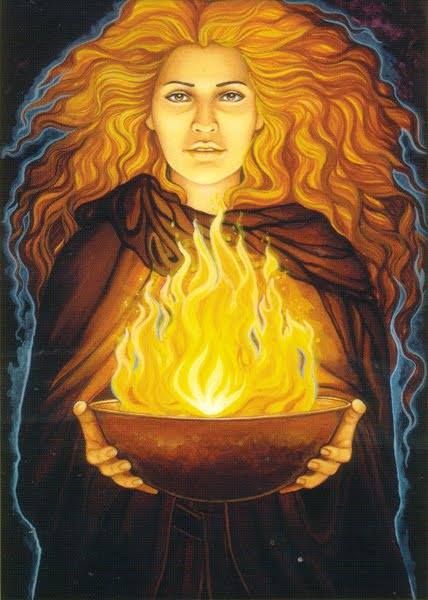

There is a special place in my heart for Brighid – perhaps it is the ancestral call of her ancient fire blazing, that potent ashless fire tended by both female Druids and by the Goddess Herself, which reawakens in me an ancient urge to create. It is true that the lore surrounding the Goddess’ important ceremonial time of year at Imbolc may sometimes be difficult for city-dwellers of the late Twentieth Century and in the Southern Hemisphere to really grasp how our ancestors felt about that time. What follows is an attempt to harness some of the inner meanings of the outer symbols associated with Brighid and to reawaken the Goddess’ ashless flame within each one who also hears Her call.

Brighid’s festival of Imbolc was traditionally celebrated during the month of February, under the auspices of the Ogham Luis (Rowan) and the fixed astrological sign of Aquarius. It is most important to take into account both the terrestrial and stellar lore associated with each of the festivals of our Druidical heritage. Each one of the ceremonies of the wheel of the year is dynamically placed so as to take full advantage of powerful surges in energy, both upon the Earth and in the Heavens, and it is the varying energies which each Festival present, that enables conscious renewal of participants in ceremony in honour of these times.

Due to our being in the Southern Hemisphere and because our seasonal cycle is at odds with the cycle in the Northern Hemisphere, many newcomers to Druidry and to other branches of the Celtic Path such as Wicca, may have a tendency to want to celebrate all the festivals in the reverse of the Northern Hemisphere cycle, but without taking into account the subtle energies associated with the times. Whilst reversing the Solstices and Equinoxes presents much less of a difficulty due to these ceremonies being conducted under the Solar ambience; the more subtle nature of the energies associated with the so-called ‘Cross-Quarter days’ – what OBOD calls the ‘Lunar-Fire festivals’ – such as Imbolc, do not so readily lend themselves to simple reversal of season. This is due to these festivals being aligned, not only to the cycle of the Sun in its waxing and waning, but more importantly, to the stellar aspects associated with the constellation which the Sun is passing through at the time of the ceremony.

Each one of the four Lunar-Fire festivals is associated with one of the four fixed signs of the Zodiac: Imbolc – Aquarius; Beltane – Taurus; Lughnasadh – Leo; Samhuinn – Scorpio. When viewed in this light, it becomes more readily apparent that much of the symbolism associated with these four ceremonies is as much drawn from (and disguising) stellar meaning, in addition to the more apparent Solar import. By simply reversing the timing of these ceremonies the inner stellar connections are most definitely broken and in some cases, the festival perhaps becomes inappropriate – an example being the difficulty of honouring the Goddess in Her ancient and death aspect (Scorpio) under the auspices of Her fecund and sexual aspect (Taurus) – which is precisely what happens when Samhuinn is celebrated in May. A similar disjunction and disruption of the flow of stellar energy into a ritual takes place when Brighid’s rite (usually an Aquarian influence) is celebrated in August (Leo).

From ongoing discussion with members of all grades over the years and the last two Assemblies, and also from discussions with practitioners of other Magickal traditions, one of the major questions, if not the first that gets brought into discussion, is whether ‘to reverse the ceremonies or not to reverse them’. This of course is entirely up to each individual and it is hoped that by such discussions and by different Members sharing their knowledge of Druidry via articles such as this, that a deeper insight into potential answers may be uncovered.

As Druid Zan Hammerton, Co-Chief of North-East Arbor Grove said in a recent conversation:

…a decision we need to individually make is whether we keep that direct connection with our ancestors and continue to perform ceremonies that were performed by them for the same reasons that they performed them – which may not have any direct relevance to our lives today – or do we rewrite the ceremonies so they have absolute meaning for us here and now?

It is very important to the continuing development of an individual’s esoteric understanding of the symbolism associated with the ceremonies that an attempt to explore the less obvious is made. It is also true, that it is because the Sun is so bright, that it obscures the more subtle stellar lore from view – and this is rightly so, at first – and whilst it is appropriate to acknowledge the Solar aspects of the ceremonies, this should not be to the detriment of acknowledging and working with the related aspects.

It is perhaps because we celebrate all our public ceremonies in the Grove of the Bards – a Grove particularly related to the Sun (ie. Outer aspects of Druidry), that members may not work with the more subtle stellar aspects. With the increase of Ovate and Druid grade members in Australia, the time is now presenting itself to initiate discussions of more inner ways of working with the ceremonies and understanding of their symbolism, fully in accordance with the energies and teachings of the Ovate and Druid Groves of the Order and our ancestral Druidic heritage. Which brings us back to Brighid and Her lore.

It was anciently said that Nineteen Druid Priestesses tended the eternal flame of the Goddess at her sanctuary at Kildare in Ireland, also called Call Dara, ‘The Church of the Oak Grove’ (from Cill ‘Church’ and Dara or as we would say, Duir, ‘the Oak’). The name of Brighid’s place resonates strongly of its ancient Druidical importance and the current St. Brigit’s Cathedral is built on an ancient axis of the Midwinter Sunrise:

There her cult took its Christian form on a prehistoric foundation. Outside the North Wall of the Cathedral, the substantial footings of her cell, a Christian fire church, are preserved, where the eternal fire, which survived until 1530, opens. (1)

Brighid’s flame has been relit in Kildare by two Christian nuns in recent years, who obviously feel the Goddess’ warmth in their hearts. Importantly, this Midwinter Sunrise axis continues on and thirty-seven miles later cuts into the south side of the tallest mountain in Leinster, called Lugnaquilla. (2) That this is a mountain associated with the harvest Sun-God Lugh and the opposite festival of Lughnasadh is apparent, as is an ancient geodetic axis.

That nineteen Druid Priestesses tended Her flame is significant. It was said that for each of nineteen nights one of these dedicated women would stand guard in sacred vigil over the flame, to prevent it dying out; but on the twentieth night, they would all gather and offer a prayer to Brighid: ‘This is your night Goddess to keep alight your hearth’. (3) Within this number, movements of both the Sun and Moon are symbolised. The Chosen Chief, Philip Carr-Gomm alluded to some of the significance of the number nineteen esoterically at the Second Australian Druid Assembly, in his talks on the lore of Taliesin and the Cauldron of Ceridwen. Suffice to say, the seemingly genteel activity of tending an ashless fire, has other more dynamic implications. This becomes much more apparent when the ancient Irish Gaelic lore and language surrounding the sacred occupation of Smithcraft is taken into account. It is perhaps not coincidental that the word for sword, ‘colg’, also may be translated into phallus. (4)

Through extended meditative research and through guidance from the Lady Herself, I have come to the conclusion that part of the ancient Mysteries of Brighid, that have been ‘lost’ due to the break in oral transmission, have to do with tending the fire of love. The art of Smithcraft, of which Brighid is Patroness Goddess, is the outer and secular form of the ancient alchemical art.Thus the ‘sword’, a life-blade in its literal sense, was ‘forged’ in the ‘hearth’ of the Goddess Herself. When considering an ancient Celtic custom, that the woman armed the young male with his weapons (an example being the tale of Arianrhod and the arming of Lleu in the fourth Branch of the Mabinogion); one begins to detect, perhaps, an ancient lore concealed beneath: of an initiation into manhood of a far more inner kind, whereby the lore of life of the eternal flame of the Goddess passed from an older Druid-Priestess to a younger Initiate. It is not coincidental that those responsible for giving birth to each generation were also in charge of instructing the sons in how to defend that generation. Those who give life are more reluctant to take it. Perhaps this is also one reason why the nineteen female Druids dedicated to Brighid lived in seclusion; to maintain the sanctity of their ‘flames’ and thereby potentise them. That Brighid’s fire is ashless is worthy of meditation in this regard. It is notable that amongst the ‘fires’ we revere in contemporary Druidry is the ‘fire of creativity’ and anciently Brighid was also considered to be the Patroness of creative activities such as the Bardic Arts of poetry, music and song. This brings consideration of the role Brighid plays with regard to all the arts associated with language in general, including speech, the magick of invocations and words of evocation, spell-crafting and oath-taking. This is particularly important, for the satire of the ancient poets contained a baleful magick, much as their beneficent songs gave forth Magickal blessings. The interlocking of the two areas of inner fire and outward expression are thus seen to be harmoniously balanced within the lore of Bride.

The celebration of Imbolc, connected as it was to the birth of new spring lambs and fresh milk following the first rains after Winter, reveals the aspect of Brighid connected to the renewal of life and also, her connection to fertility magick. This aspect of the Goddess was celebrated by the decoration and honouring of local wells and the giving of offerings of new milk and white cloths left outside to collect the dew on the Eve of Imbolc. It is through such ancient offerings, that part of the symbolism of Imbolc and the connection to the signs of Aquarius and Ogham Luis is revealed.

From Babylonian times, the sign for Aquarius has always been a human figure holding a large urn, or vessel of water, from which the waters flow forth freely. In ancient minds what this symbolises was also seen in a humble well – a source of life-giving water for the living. This connection to water is also evident from the Song of Amergin, where the time in which Imbolc falls is called “I am a wide flood plain”. (5) Interestingly, we still use the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for waters as the glyph for the sign of Aquarius. This connection of water and wells, milk and dew, all life-giving fluids of both element, animal and plant find their symbolic counterparts within the human body. The connection of Brighid to human fertility is most apparent in the continuation of the custom of honouring women who have just given birth through the lighting of candles (Candlemas).

However, Imbolc falls under the auspices of a celestial vessel and stellar waters. These are the waters of wisdom, and a key to the connection of Imbolc to this sign is that what the individual receives through the tutelage of Brighid is to be given forth freely to others. Brighid, Patroness of many arts: both Bardic – smithcraft, music, poetry and song; Ovate – in the use of healing plants and tinctures and Druid – in the understanding of the appropriate use and direction of life-energies; can thus be appreciated as a wise and beneficent Goddess, whose lore brings to birth joy, healing and indeed, ancestral wisdom for modern-day practitioners. Her protective influence around the path may be felt through the Rowan Ogham and similarly, the ‘weapons’ we are armed with in Her service.

Endnotes:

1. DAMES, Michael – Mythic Ireland. Thames and Hudson, London 1992 p.231 2. Ibid, p.232.3.

Teaching from a contemporary Australian Priestess of Brighid with the Fellowship of Isis, 19934. DAMES, opp. cit., p.1105.

NICHOLS, Ross. The Book of Druidry, The Aquarian Press, London, 1990. pp.290.

More on Imbolc

Imbolc

Imbolc ~ This Tender Blooming

Brigit

Rekindling the Fire

Imbolc online: Meditations & Explorations