by Winter Cymres ~

by Winter Cymres ~

I am She

that is the natural

mother of all things,

mistress and governess

of all the elements,

the initial progeny of worlds,

chief of the powers divine,

Queen of all that are in the otherworld,

the principal of them

that dwell above,

manifested alone

and under one form

of all the Gods and Goddesses.

– Lucius Apuleius

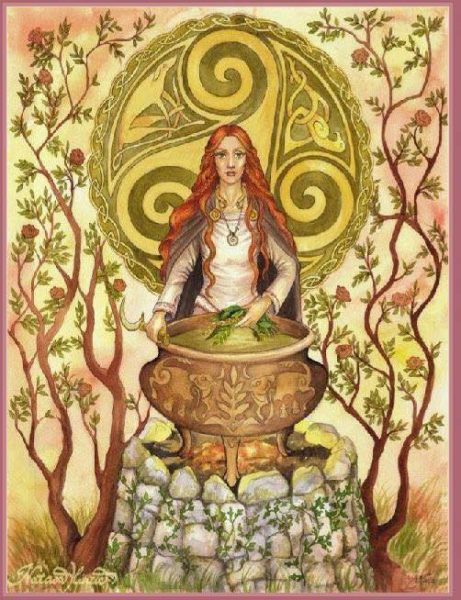

Perhaps one of the most complex and contradictory Goddesses of the Celtic pantheon, Brigid can be seen as the most powerful religious figure in all of Irish history. Many layers of separate traditions have intertwined, making Her story and impact complicated but allowing Her to move so effortlessly down through the centuries. She has succeeded in travelling intact through generations, fulfilling different roles in divergent times.

She was, and continues to be, known by many names. Referred to as Bride, Bridey, Brighid, Brigit, Briggidda, Brigantia, I am using Her name, Brigid, here. There are also many variations on pronunciation, all of them correct, but, in my own mind, I use the pronunciation, Breet.

The patroness of healing, poetry and smithcraft

Brigid is the traditional patroness of healing, poetry and smithcraft, which are all practical and inspired wisdom. As a solar deity Her attributes are light, inspiration and all skills associated with fire. Although She might not be identified with the physical Sun, She is certainly the benefactress of inner healing and vital energy.

Also long known as The Mistress of the Mantle, She represents the sister or virgin aspect of the Great Goddess. The deities of the Celtic pantheon have never been abstraction or fictions but remain inseparable from daily life. The fires of inspiration, as demonstrated in poetry, and the fires of the home and the forge are seen as identical. There is no separation between the inner and the outer worlds. The tenacity with which the traditions surrounding Brigid have survived, even the saint as the thinly-disguised Goddess, clearly indicates Her importance.

As the patroness of poetry, filidhecht, the equivalent of bardic lore, are the primal retainers of culture and learning. The bansidhe and the filidh – Woman of the Fairy Hills and the class of Seer-poets, respectively, preserve the poetic function of Brigid by keeping the oral tradition alive. It is widely believed that those poets who have gone before inhabit the realms between the worlds, overlapping into ours so that the old songs and stories will be heard and repeated. Thus does Brigid fulfill the function of providing a continuity by inspiring and encouraging us.

The role of the smith in any tribe was seen as a sacred trust and was associated with magickal powers since it involved mastering the primal element of Fire, moulding the metal (from Earth) through skill, knowledge and strength. Concepts of smithcraft are connected to stories concerning the creation of the world, utilizing all of the Elements to create and fuse a new shape.

Brigid is also the Goddess of physicians and healing, divination and prophecy. One of Her most ancient names is Breo-saighead meaning fiery arrow, and within that name is the attribute of punishment and divine justice.

Associations

Three rivers are named for Her – Brigit, Braint and Brent in Ireland, Wales and England, respectively. In modern Britain

today She is shown as the warrior-maiden, Brigantia, and venerated not only as justice and authority in that country, but also as the personification of Britain as is seen on the coin of the realm. There is a story, coming from the 12th century, in which Merlin is inspired by a feminine figure who represents the sovereignty of the Land of Britain. She causes his visions to reach through British history, on, so it is said, to the end of the solar system. Taliesin also describes a traditional cosmology, inspired by Brigantia. She is central to many heroic myths, especially those concerned with underworld quests and sacred kingship. This seems to relate to Her concern for the development of human potential.

Her important association with the cow, coupled with its critical necessity in Celtic culture and history, relates to the festival of Imbolc. This celebration, which is so completely Hers, involves itself with the lighting of fires, purification with well water and the ushering in of the new year (Spring) by a maiden known as the Queen of the Heavens. The significance of Imbolc is so deep that it deserves an entire section within any work relating to Brigid.

To fully grasp the significance of Imbolc it is necessary to understand the life-and-death struggle represented by winter in any agrarian society. In a world lit only by fire the snow, cold and ice of this season literally holds you in its grip, only relaxed with the arrival of spring. Although the Equinox does not arrive until later and spring is celebrated with Ostara and Beltane, Imbolc is the harbinger and the indication that better times are coming.

During the cold months, certain issues become pressing. Is there enough food for both humans and animals? Will illness decimate the tribe, especially in the case of the young, the old and nursing mothers? And what of the animals whose lives are so crucial to our own? One of the most burning questions would be with the pregnant cows and ewes since their milk is used for drink, for cheese and curds which might mean the difference between life and death.

By Imbolc these animals will have birthed their young and their milk would be flowing. Milk, to the Celts, was sacred food, equivalent to the Christian communion. It was an ideal form of food due to its purity and nourishment. Mother’s milk was especially valuable, having curative powers. The cow was symbolic of the sacredness of motherhood, the life-force sustained and nourished. This was not a passive cow giving milk but an active mother fighting for the well-being of her children.

Imbolc divides winter in half; the Crone months of winter are departing and the promise of the Spring Maiden is around the corner. This holiday eventually became modern day Candlemas with Saint Brigid’s Day and the Feast of the Purification of Mary being celebrated during this period of time. This celebration was definitely a feminine festival. Women would gather to welcome the maiden aspect of the Goddess as embodied by Brigid. Corn cakes made from the first and last of the harvest were made and distributed and this practice remains a part of Her celebration. During these festivities, She was commonly represented by a doll, dressed in white, with a crystal upon Her chest.

This doll, usually a Corn Dolly, was carried in procession by maidens also dressed in white. Gifts of food were presented to the Goddess with a special feast given by and for the maidens. Young men were invited to this feast for the purpose of ritual mating to insure that new souls would be brought in to replace those lost during the cold times.

The holiday has pastoral connections due to the association of the coming into milk of the ewes. Although Brigid is designated as an all-encompassing deity during Imbolc, She is honored in Her capacity as the Great Mother. She possesses an unusual status as a Sun Goddess Who hangs Her Cloak upon the rays of the Sun and whose dwelling-place radiates light as if on fire. Brigid took over the Cult of the Ewes formerly held by the Goddess Lassar, who also is a Sun Goddess and who made the transition, in the Isles, from Goddess to saint. In this way Brigid,s connection to Imbolc is completed, as the worship of Lassar diminished, only to be revived later in Christian sainthood.

She possesses an unusual status as a Sun Goddess Who hangs Her Cloak upon the rays of the Sun and whose dwelling-place radiates light as if on fire. Brigid took over the Cult of the Ewes formerly held by the Goddess Lassar, who also is a Sun Goddess and who made the transition, in the Isles, from Goddess to saint. In this way Brigid,s connection to Imbolc is completed, as the worship of Lassar diminished, only to be revived later in Christian sainthood.

Brigid long transcended territorial considerations, providing some unity between the warring tribes in Western Europe and the Isles. Her three sons gave their names to the soldiers of Gaul. The cult of Brigid exists not only in Ireland but throughout Europe as well; She has an ancient and international ancestry, Her name meaning, high or exalted. As Mother Goddess, Brigid united the Celts who were spread throughout this area. She was the one feature upon which they all agreed, no matter how disparate they were in location or traditions.

In addition to Her totemic animals of the cow and the ewe, She is also associated with the cockerel, the herald of the new day and the snake, symbol of regeneration. In this way She is related to fertility Goddesses, many of Whom were also shown holding snakes and shares with Minerva the shield, spear and crown of serpents. Serpents are also a common theme in Celtic jewellery (another product of smithing) with many torcs displaying this sinuous symbol of power and divinity.

Brigid stories

Her stories retain remnants of other Goddesses from the ancient worlds and the worship at Her later convent at Kildare was said to resemble that of Minerva. Some of Her symbols are identical to the Egyptian Goddess, Isis. Her embroidery tools, which are also Minerva‚s symbols, were preserved at the chapel at Glastonbury, along with Her bag and Her bell, symbolic of healing. Her colours – white, black and red – are those of Kali and show an ancient connection there.She began as a triplicity of sisters, not unusual to Celtic lore. She is the Daughter of Dagda and the Morrighan and sister to Ogma, a Sun God and the Creator of the Ogham. With Bres of the Fomorians, She had three sons – Brian (Ruadan), Iuchar and Uar – and Brian’s actions in The Battle of Moytura figure largely in Her evolution to a Goddess of Peace and Unity.

To understand the significance of this battle it is necessary to know a little bit about Celtic tradition concerning family. Matrilineal, it meant that ancestry was traced through the mother’s line rather than the father’s; the most important male in your life would be the oldest male kin to your mother, often an uncle and not necessarily a grandfather since his lineage to her may not exist. All blood relationships of any importance came through your mother’s line. This tie was so tight that children of sisters were considered to be siblings rather than cousins.

Motherhood demanded the utmost reverence. Rape was a crime of highest severity, subject to the greatest punishments and not pardonable or subject to leniency (Later, in Her evolved role as the Lawgiver, Brigid would make certain that women’s rights were retained in some form within the new religion).

The marriage of Brigid to Bres was essentially an alliance to bring peace between two warring factions. She was of the Danu and he of the Fomorians. With the intermarriage, war was hopefully averted. Ruadan, Brigid’s eldest son, used the knowledge of smithing given to him by his maternal kin, the Danu, against them by killing their smith, a sacred position within the tribe. This smith killed Ruadan before dying himself. Brigid’s grief and lamentations were said to be the first heard in Ireland and were not only an expression of mourning for the loss of Her son but also for the enmity between maternal and paternal factions of family.

This was seen as the beginning of the end for the Old Ways. And so, the Irish story of Original Sin‚ was the act against maternal kinship rather than that of sexuality since sexuality, which brings the sacred position of motherhood, was seen as positive by the Celts.

Her evolution

Her evolution from Goddess to saint linked Pagan Celtic and Christian traditions much the same way the Cauldron of Cerridwen and the Holy Grail were combined in Arthurian legend. She acts as a bridge between the two worlds and successfully made the transition back to Goddess again with most of Her traditions retained. The worship of Saint Brigid has persisted up until the early 20th century with Her Irish cult nearly supplanting that of Mary. She is commemorated in both Ireland and the highlands and islands of Scotland.

In order to incorporate Brigid into Christian worship, and thus insure Her survival, Her involvement in the life of Jesus became the stuff of legend. According to the stories in The Lives of the Saints, Brigid was the midwife present at the birth, placing three drops of water on His forehead. This seems to be a Christianized version of an ancient Celtic myth concerning the Sun of Light upon Whose head three drops of water were placed in order to confer wisdom.

Further, as a Christianized saint, Brigid was said to be the foster-mother of Jesus, fostering being a common practice among the Celts. She took the Child to save Him from the slaughter of male infants supposedly instigated by Herod. She wore a headdress of candles to light their way to safety.

There exists an apocryphal gospel of Thomas that was excluded from the Bible in which he claims a web was woven to protect the infant Jesus from harm. This is in keeping with Her status as the patron of domestic arts, weaving wool from Her ewes, increasing the connections as a pastoral Goddess.

Due to the original differences between the Roman church and that which was once an extremely divergent type of Christianity practiced in the Western Isles, particularly Ireland, many of the older deities made the transition from Gods and Goddesses to saints, some experiencing Church-inflicted gender changes on the way.

Often thinly-disguised pagan worship was continued in monasteries and convents which were built on or near the sites sacred to the Celtic pantheon. Many of the great monasteries – Clonmacnoise, Durrow and Brigid’s own Kildare – were great centres of learning and culture, with information disseminated from these sites to Western Europe (This is much the same as the great Druidic colleges and it is not surprising to find that places sacred to the new religion were built upon the foundations of the old).

These cloisters are thought to have kept alive and preserved much of classic culture in Europe throughout the Dark Ages. During this period of time, wars were decimating the population. Mary, as the Mother in this new religion, was embraced by women who felt a similar experience of sacrificing their sons to a political and religious machine.

The Triple Goddesses were replaced by a Trinity, but the Old Ways lingered in worship. Brigid’s role as Mother Goddess was never completely eradicated and reappears throughout Her entire career as a Catholic saint. As Saint Brigid, there are rays of sunlight coming from Her head, as portrayed as a Goddess. Themes of milk, fire, Sun and serpents followed Her on this path, adding to Her ever-growing popularity. Compassion, generosity, hospitality, spinning and weaving, smithwork, healing, and agriculture ran throughout Her various lives and evolution.

Her symbolism as a Sun Goddess remains, also, in the form of Brigid’s crosses, a widdershins or counter-clockwise swastika, found world-wide as a profound symbol, reaching Ireland by the second century B.C.E, and is still used there today to protect the harvest and farm animals.One of the stories of Her life as a saint supports Her original attribute as a solar deity. During Her infancy the neighbours ran to Her house, thinking it was afire. This radiance came from the infant saint, a demonstration of Her grace bestowed as by the holy Spirit. A prayer to Saint Brigid requests,

Brigit, ever excellent woman,golden sparkling flame,lead us to the eternal Kingdom,the dazzling resplendent sun.

Even in Her new incarnation as a Catholic saint Her previous existence is affirmed. The eternal flame at Her convent at Kildare suggests its existence as having been pagan and/or Druidic. The shrine at Kildare is assumed to be a Christian survival of an ancient college of vestal priestesses who were trained and then scattered throughout the land to tend sacred wells, groves, caves and hills. These priestesses were originally committed to thirty years in service but, after this period, were free to marry and leave. The first ten years were spent in training, ten in the practice of their duties and the final ten in teaching others, similar to the three degrees of initiation found in most traditions.

These women preserved old traditions, studied sciences and healing remedies and, perhaps, even the laws of state. At Kildare their duties must have involved more than merely tending the fire. This perpetual fire at the monastic city was tended by nineteen nuns over a period of nineteen days. On the twentieth day, Brigid Herself is said to keep the fire burning.

The site for the monastery at Kildare was chosen for its elevation and also for the ancient Oak found there, considered so sacred that no weapon was permitted to be placed near it, with fines collected for the gathering of deadfalls within its area. The word, Kildare, comes from ‘Cill Dara’, the Church of the Oak. The entire area was known as Civitas Brigitae, ‘The City of Brigid’.

The preservation of the sacred fire became the focus of this convent. The abbess was considered to be the reincarnation of the saint and each abbess automatically took the name, Brigid, upon investiture. The convent was occupied continuously until 1132 C. E., with each abbess having a mystical connection to the saint and retaining Her name. At this point, Dermot MacMurrough wished to have a relative of his invested as the abbess. Although popular opinion was against him, his troops overran the convent and raped the reigning abbess in order to discredit her.

After this, Kildare lost much of its power and the fires were finally put out by King Henry VIII during the Reformation. During the time the convent was occupied by the saint Herself, She went from the position of Mother Goddess to that of Lawgiver, paralleling Minerva, once again. Her ability to move between categories is the secret of Her continuing success. When the laws were written down and codified by Christianity, Brigid figured largely to insure that the rights of women were remembered. These laws had been committed to memory by the brehons as a part of the extensive oral tradition.

The Old Ways were still practiced, although not often openly and, in order to make certain that people would not stray from the new religion, many aspects of the old were incorporated into the new. In keeping with the Old Ways, men were not permitted to impregnate women against their will, against medical advice or the restrictions of her tribe. A man was not permitted to neglect the sexual needs of his wife. Irish law also provided extensively for the rights of women in marriage, for pregnancy out of wedlock‚ and for divorce. In one incident, clearly defining the position of women in this new warrior class, a woman petitioned Brigid for justice. Her lands and holdings were about to be taken from her after the death of her parents. Brigid, however, ruled that it was the woman’s decision to either take the land as a warrior, being prepared to use arms to protect her holdings and her people. If she decided not to take on this privilege‚ half her land should go to her tribe. But, if she chose to hold the land and support it militarily, she was permitted to hold the land in its entirety.

In one incident, clearly defining the position of women in this new warrior class, a woman petitioned Brigid for justice. Her lands and holdings were about to be taken from her after the death of her parents. Brigid, however, ruled that it was the woman’s decision to either take the land as a warrior, being prepared to use arms to protect her holdings and her people. If she decided not to take on this privilege‚ half her land should go to her tribe. But, if she chose to hold the land and support it militarily, she was permitted to hold the land in its entirety.

The shift from Mother Goddess to Virgin Mother to Virgin Saint presented difficulty. Even though it insured Her survival and the emergence of Her power in Neo-Paganism, the emphasis on virginity stemmed completely from the Christian patriarchy. She derived power at the expense of other women, removing motherhood from its revered position in Celtic society.

As the Mother, Brigid keeps the traditions alive and whole, offering a means of guidance that sustains through any circumstances. In Her capacity as the Lawgiver, Her attempts to carry the Old Ways through the storm to the present day, much as Merlin’s work would extend to the limits of the solar system, have been successful. Paganism still exists and in a form that may well weather the storms present at this moment.

However, seeing Brigid as the unbroken vessel, Her virginity being wholly symbolic, Her loyalty is not compromised by allegiance to one lover or husband. Beyond the grip of any one tribe or nation, She can mediate to ensure unity for the good of all. She protects us as we walk through the labyrinth but also makes us face the reality of ourselves. Her Fire is the spark alive in every one of us.