by Kennan Elkman Taylor

Historically the runes stem from the Teutonic regions, considered as mainly modern-day Germany, early in the Common Era (CE); although some commentators would see their origins to be many centuries earlier. In fact, the runes may represent an unbroken tradition from the Stone Age, as cave drawings and other preserved objects have painted and etched symbols with a runic quality. If so, they arise with the dawn of human consciousness and its evolution, representing an ancient means of communication.

By the time the runes emerged historically, the Celts, also a Teutonic people, had migrated to Britain (500 before the Common Era, or BCE) and developed their own culture there, with input from the indigenous peoples they superseded. At the start of the Common Era (CE) the Celts themselves were superseded by the Romans, in much of what is now present-day England.

Meanwhile, within Germany, many tribes were preparing to migrate and expand `their influence. So, after the Roman departure in the 5th century CE the vacuum in England was filled by Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, collectively referred to as the Anglo-Saxons. They brought the early runes with them, which at this time had settled into an ‘alphabet’ of sorts. This rune row, or the linear sequence of runes, was called the Elder Futhark and comprised 24 runes, so named after the first six runes (‘th’ is one rune).

The Anglo-Saxons were relatively confined to England and evolved into what we know now as the English race. Ireland, Wales and the West of England remained more Celtic, as did Scotland with the Picts and Scots. This should be considered a very fluid state of affairs; although our interest is marked by runic finds, which tend to be almost exclusively in the regions occupied by the Anglo-Saxons.

In these so-called Dark Ages the runes took on a distinctly English character and extra runes were added to the Elder Futhark’s 24 runes. These extra runes number between 4 and 5. Around the 8th and 9th centuries a further expansion of the Futhorc occurred in Northumbria so that there were now 33 runes in total. Also with a change of the 4th and 6th runes in name, shape, and phonetic expression, the Elder Futhark became in time the Anglo-Saxon or Old English Futhorc.

Over this same period the Anglo-Saxon language developed and adopted the Roman script to become Old English. Although the runes have phonetic values that could be used for writing, this did not generally occur, except as inscriptions. This may be due to the fact that the runes always had a magical component, so were increasingly and more exclusively used in this way; whereas the Roman script under Christianisation, lacking this dimension, became more suitable and available for everyday usage.

This more magical association of the runes is detected in the later runes of the completed Futhorc. It is also apparent in the Viking era between 800 CE and 1100 CE when, in Northern Germany and Scandinavia, the rune row of the Elder Futhark underwent a reduction to 16 runes and being subsequently known as the Younger Futhark. This may have been an attempt to re-establish the more magical use of the runes in the face of the progressive Christianisation that was occurring during this period. With the completion of Christianisation in Scandinavia the Viking era came to a close around 1100 CE.

In Britain, Christianisation had been a lot earlier, properly beginning in the 7th century, although present before then. Christianity provided a significant cultural influence, but seemingly ignored the runes (perhaps due to denial, repression, exorcism, or all of those things), with the exception of the Northumbrian input. Influences from the Celtic era may be seen in the 4 to 5 runes that developed immediately after colonisation, as trees are strongly present. It is thought that the Celts and their priesthood, the Druids, used a magical system called Ogham that was based on trees.

In Britain, Christianisation had been a lot earlier, properly beginning in the 7th century, although present before then. Christianity provided a significant cultural influence, but seemingly ignored the runes (perhaps due to denial, repression, exorcism, or all of those things), with the exception of the Northumbrian input. Influences from the Celtic era may be seen in the 4 to 5 runes that developed immediately after colonisation, as trees are strongly present. It is thought that the Celts and their priesthood, the Druids, used a magical system called Ogham that was based on trees.

After the close of the Viking era, runes and the various Futharks (a collective term comprising all three rune rows) disappeared from public view. However, this was not true of traditions within these now Christian cultures that held to the ‘old ways’, and also in the folk traditions there. Obviously the runes never completely died out, making occasional appearances, until the increasing interest and re-emergence over the last few centuries.

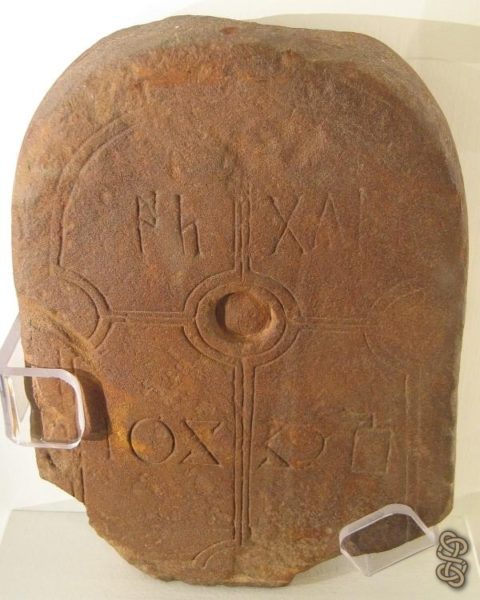

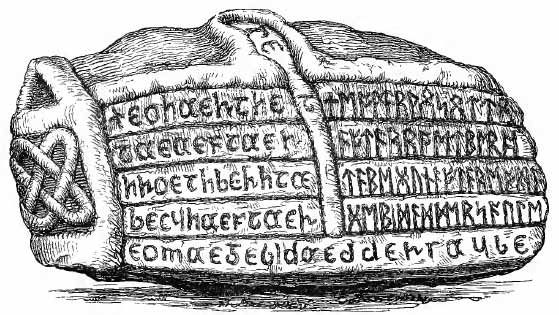

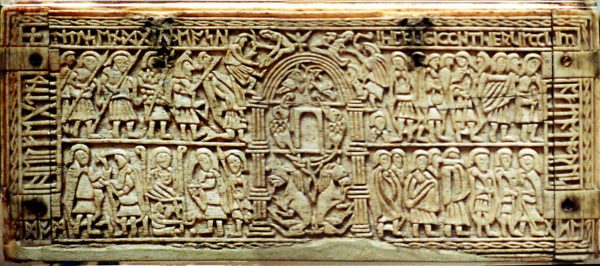

We know of the runes through archaeological finds. These are on ornaments, coins, stones, and in manuscripts. They were probably more commonly and magically used on materials that could be sacrificed and would not have survived anyway, such as wood. Collectively these give us the rough outlines that have fleshed out all of the Futharks. But there is collateral evidence regarding runes that extends to their meanings and, although being handed down from Christian scribes, there exists what are known as rune poems.

The Old English rune poem of the 8th or 9th century survived in its original manuscript form until being destroyed in a fire in the 18th century. Luckily a copy was made some years prior, with the additional inscription and assignment of actual runes to each of the 29 poems. Although a later interpolation, there is good evidence to support its validity and the associations are generally accepted in the academic community.

In the Viking era the rune poems of the Younger Futhark were written down in two versions, firstly the Icelandic version in the 13th century, with the Nordic following a couple of centuries later. Again these were by a Christian hand, but they serve to corroborate the Old English poem, even though the poems (or riddles) themselves are often quite different in context. Unfortunately there is no equivalent rune poem for the Elder Futhark.

In the Viking era the rune poems of the Younger Futhark were written down in two versions, firstly the Icelandic version in the 13th century, with the Nordic following a couple of centuries later. Again these were by a Christian hand, but they serve to corroborate the Old English poem, even though the poems (or riddles) themselves are often quite different in context. Unfortunately there is no equivalent rune poem for the Elder Futhark.

We now have several levels of potential meaning in the runes. There is the pictorial representation that is itself symbolic. Assisted by the mixture of Roman and runic scripts over time we also have a definite phonetic sequence, as well as names for each rune, themselves of symbolic significance. The rune poems add another level of meaning, often in what could traditionally be seen as riddles or charms.

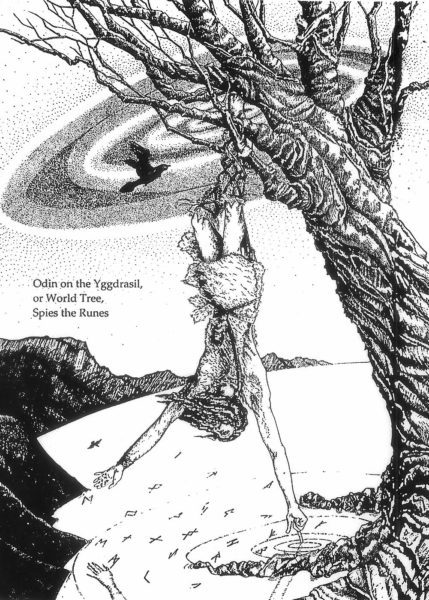

Indeed, a poem sourced in the Icelandic Poetic Edda of the Viking era, called the Havamal, describes the god Odin (Woden in Old English) obtaining the runes by an act of self-sacrifice, where he also utters eighteen charms associated with them. The significance here, as the charms do not readily correlate with specific runes, is the relationship of Teutonic mythology to runology. Additionally, Odin’s act is sacrificial in a manner not dissimilar to Christ on the cross, and which we would now call shamanic.

There is much more evidence available than in this simplified version, quite obviously, but nothing that contravenes this brief outline. In fact, the whole academic and scholarly field is awaiting further finds to fill in the gaps and to adjust our thinking on the subject.

In the modern era we have rediscovered the runes and are also rediscovering their significance, but is this just a historical accident? I think not. I consider it may be what is known as the ‘return of the repressed’ on a collective level. With the decline of Christianity as a spiritual influence and the waning of the Church’s political and cultural control, the runes are resurfacing with other cultural reconnections (of which the New Age is replete, in content if not always in accuracy).

In the modern era we have rediscovered the runes and are also rediscovering their significance, but is this just a historical accident? I think not. I consider it may be what is known as the ‘return of the repressed’ on a collective level. With the decline of Christianity as a spiritual influence and the waning of the Church’s political and cultural control, the runes are resurfacing with other cultural reconnections (of which the New Age is replete, in content if not always in accuracy).

Many of us have an Anglo-Saxon heritage. If that is the case then it is most likely that spiritual traditions from your heritage and their more magical tools will strike an internal resonance. This is primarily emotional and a feature of anything returning from a personally repressed position, although this emotional feeling is deeper and more psycho-spiritual if it is collective and from our heritage.

In the modern era we have also focussed a lot on the Elder Futhark, and this has greatly facilitated this rediscovery process. However, there is the extant and distinctly Anglo-Saxon rune row that has not, in my opinion, been fully explored. That is why I am using the Futhorc exclusively here; though not without reference to the other two Futharks, their significance, and the traditions they came from.

Within the Christian tradition the concept of ‘soul’ has become marginalised, although this term is in dire need of restoration, as many moderns are looking for a more ‘direct’ spiritual connection. In a sense this is where the more esoteric traditions within established religious structures are resurfacing, as well as those from other traditions. We are familiar with such eastern influences; it is time to look in our own backyard.

Within the Christian tradition the concept of ‘soul’ has become marginalised, although this term is in dire need of restoration, as many moderns are looking for a more ‘direct’ spiritual connection. In a sense this is where the more esoteric traditions within established religious structures are resurfacing, as well as those from other traditions. We are familiar with such eastern influences; it is time to look in our own backyard.

To my mind the runes fulfil this function for many. The soul is asking firstly for her own voice, and secondly for a path back to the divine. In less mystical terms this is establishing a relationship with the greater reality that pervades and permeates our very existence. This relationship has a language that is necessarily symbolic and imaginative. Not only do the runes fulfil this criterion, it may be that the ‘greater reality’ itself is using them as a means for getting back in contact with its ‘lost children’.

Poetic and spiritual metaphors notwithstanding, the runes are a magical system par excellence. They are rich in meaning, challenging to work with, and make demand on our morals asking us to fulfill our individual fate, or what the Teutonic peoples refer to as ‘wyrd’.

Futhorc is the ‘Brief Introduction’ from Kennan’s forthcoming book on the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc Just Add Blood published by John Hunt Publishing.