by Bill Blank

There is a Romano-Celtic solid bronze votive in the form of the helmeted head of Minerva (1st century CE, 1.5″, 3.8 cm tall). Intensely stylized, she wears a high crested helmet decorated on either side with dolphins. Her hair falls in locks at the perimeter of her helmet. Her facial detail, including her wide eyes, broad nose and tightly closed lips, is strongly preserved. She wears an ornamental breastplate that ironically mirrors her own expression. This figure is an example of bronze votive Roman art as influenced by the native Celts of Britain. The eyes, and particularly the breastplate, are predominately Celtic in design.

One of the unique features of this example is the breastplate which mirrors the goddess’ serious facial expression. Also, the sculpting of the helmet is zoomorphically styled with the dolphin heads. There are three similarly-sized bronze Minerva busts on display in the British Museum. This particular example is in my own collection.

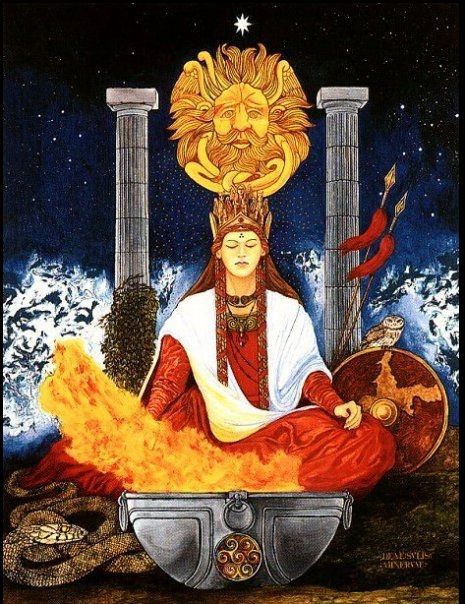

Minerva was the Roman goddess of war, wisdom and the crafts. In Britain at the turn of the 1st millennium CE, Minerva was depicted throughout Celtic Britain in both purely Roman fashion and in the more abstract Celtic style as illustrated above. But in Bath, at the temple of Aquae Sulis she becomes ‘fully equated with a Celtic goddess, Sulis’. (1)Sulis was a local goddess of healing who ruled over the remarkable hot spring beside the river Avon near Bath (Aquae Sulis). She was not only a water deity, but her name Sulis is obviously linked with the sun, probably related to the heat of the waters. Thus she represents two of the elements, water and fire. Her association with Minerva may have related with the craft of healing. Miranda Green says,

The shrine of Sulis Minerva at Bath provides a superb example of the conflation and hybridization of Roman and Celtic religious beliefs and practices. On epigraphic dedications to the goddess where both Celtic and Roman names are mentioned, that of the indigenous goddess, Sulis, is always put first, thereby emphasizing that she was the patroness of the spring and that her cult was long standing. (2)

Perhaps the most famous image from Aqua Sulis is the masculine Medusa head on the main temple pediment. This is a most remarkable image relating the classical Greek myth of Perseus and the Gorgon with the Celtic goddess Sulis and, by inference, the Roman goddess Minerva. The Celtic influence in this image has transformed the female gorgon into a male, bearded face. The locks of hair can represent not only waves of the sea, but also rays of the sun, again linking both fire and water to the sacred spring. Snakes in the beard leave little doubt of the Medusa relationship. Wings on each side of the head suggest a relation with air and the stone of the figure with earth. Thus this single Celtic image combines the four elements – earth, air, fire and water – in a composite whole which hearkens from the Celts through the Romans to the Greeks and, as a predecessor to the future Greenman.

The Legend of Catumandus

The Greek colony, Massilia (now Marseilles) was founded in the early 6th century BCE near to what was to become the Celtic heartland. The Celts, as they developed, had generally good trading relationships with the Massalians with minor skirmishes won by the Massalians. However, in the early 1st century BCE, one Catumandus, meaning ‘general’ or ‘he who directs battle’ (cf. Irish cath and Welsh cad , battle), chieftain of the Saluvii centered on what in now Entremont, attacked Massilia. As reported by Pompeius Trogus, he saw ‘a vision of a menacing women who told him that she was a goddess’ whom Catumandus took to be one of the Celtic triple goddesses of death and war (cf. the later Irish Morrigu, The Morrigan). She warned him against continuing the attack.

Catumandus broke off his attack, sued for peace with the Massialians and asked if he could enter the city and worship their gods:

According to Trogus, he recognized a statue of a goddess at the portico of the temple of Minerva and claimed it was the very woman he had seen in his vision. He therefore presented his gold torque, his necklace symbolizing his rank, as a sacrifice to the goddess and swore a treaty of perpetual friendship with the city. (3)

Although Trogus reports this story, it certainly has the feel of legend or myth. It also suggests, however, that the Celts had encountered Minerva long before the Romans invaded the Celtic world and had probably incorporated here into their pantheon by whatever name.

References:

1. The Gods of Roman Britain, Miranda Jane Green, Shire Archaeology, 1993, ISBN: 0852636342, pp.29-31

2. Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend, Miranda J. Green, Thames & Hudson, 1992, ISBN: 0-500-01516-3, pp.200-202

3. Celt and Greek: Celts in the Hellenic World, Peter B. Ellis, Constable, 1997, ISBN#: 0-09-475580-9, p. 50