by Andrew Peers

by Andrew Peers

Seated at a heavy wooden table in front of the old presbytery window, I can look away from the village onto green fields and stately mature oak trees. It is autumn and their leaves are turning yellow and orange. This village in Gelderland lies in an area particularly associated with oaks. Observing the quiet change in the season and silently tuning in to its rhythm, is, broadly speaking, what is understood as “Celtic” in the Celtic School of Buddhism. It is the felt connection to the natural world as it continually moves on, a way of simply learning to move with it, even to celebrate it as the dance of transience in the mandala of nature.

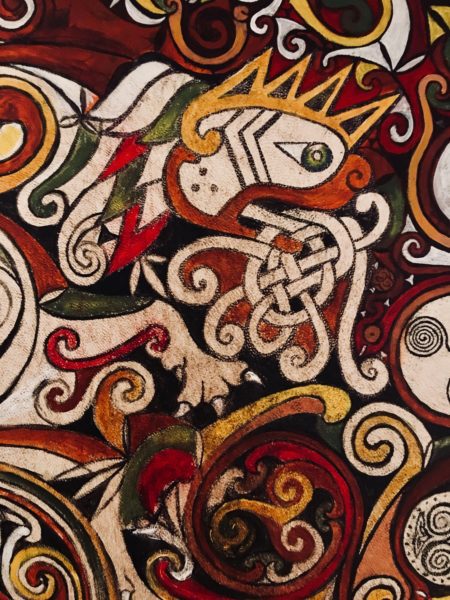

The Celts in their day did not generally live into ripe old age but this did not make them fatalistic or depressed. Their culture and art testify to this. They were warriors familiar with the struggle to survive, with the threat of enemies and war, and their songs and legends have a brassy, bragging heroic tone of a people proud of their banditry and in love with their own eloquence. For them, life and death were interwoven, with many “thin places” between the two. They were spread throughout Western Europe and lived once here too among the old oaks of Gelderland.

I am reminded of the time when, still a Trappist monk living in Northern Ireland, I went to the abbey shop one day and was confronted in the entrance passage by a poster on the wall showing about twenty gargoyle-like faces. “The River Gods of Ireland” it proclaimed. How on earth, I thought to myself then, could a poster like that be hanging in the shop of a Roman Catholic abbey? And who do those faces belong to, where do they live? The late Chögyam Trungpa, an influential Tibetan Buddhist teacher of meditation and founder of the Celtic School of Buddhism, saw these local energies and gods as the Western equivalent of the gods of the native Tibetan religion called Bön. In the rivers and in the air, they are associated with special places in nature. In Tibet, the more war-like gods go by the name of dralas. The word “drala” is connected to “deity” and signifies simultaneously both a natural force operating in the phenomenal world and an aspect of our own pure awareness. Trungpa was deeply saddened by the loss of the great drala traditions of Europe. In this tradition, the spiritual path is portrayed as a field of battle where pitfalls are the kind of threats that the Celtic heroes met in their epic contests: the poison of arrogance, the trap of doubt, the ambush of hope and the arrow of uncertainty. Here the enemy is the ego and its projections. The greatest weapon is openness, endless patience has immediate effects, and victory is the victory over war and aggression. Dra means ‘enemy’ or ‘opponent’, La means ‘above’. Drala therefore means the wisdom above or beyond aggression, beyond the ego.

The late Chögyam Trungpa, an influential Tibetan Buddhist teacher of meditation and founder of the Celtic School of Buddhism, saw these local energies and gods as the Western equivalent of the gods of the native Tibetan religion called Bön. In the rivers and in the air, they are associated with special places in nature. In Tibet, the more war-like gods go by the name of dralas. The word “drala” is connected to “deity” and signifies simultaneously both a natural force operating in the phenomenal world and an aspect of our own pure awareness. Trungpa was deeply saddened by the loss of the great drala traditions of Europe. In this tradition, the spiritual path is portrayed as a field of battle where pitfalls are the kind of threats that the Celtic heroes met in their epic contests: the poison of arrogance, the trap of doubt, the ambush of hope and the arrow of uncertainty. Here the enemy is the ego and its projections. The greatest weapon is openness, endless patience has immediate effects, and victory is the victory over war and aggression. Dra means ‘enemy’ or ‘opponent’, La means ‘above’. Drala therefore means the wisdom above or beyond aggression, beyond the ego. Celtic tribes were warrior tribes, and it is this basic attitude of daring that the Celtic School of Buddhism first and foremost seeks to rekindle with regard to spiritual development in modern life today. Life is still short enough, and a pro-active warrior-like bravery can serve it best. Working with spiritual realities of another order also introduces the shamanic aspect of Celtic Buddhism. The shaman in the tribes of the Celts was known as a druid. The name “druid” has been translated “knower of the oak” and it is said that apprenticeship to a druid could take as long as twenty years. A question that surfaces in my mind on this sunny autumn morning, as I look out at these impressive oaks, is: what exactly took so long?

Celtic tribes were warrior tribes, and it is this basic attitude of daring that the Celtic School of Buddhism first and foremost seeks to rekindle with regard to spiritual development in modern life today. Life is still short enough, and a pro-active warrior-like bravery can serve it best. Working with spiritual realities of another order also introduces the shamanic aspect of Celtic Buddhism. The shaman in the tribes of the Celts was known as a druid. The name “druid” has been translated “knower of the oak” and it is said that apprenticeship to a druid could take as long as twenty years. A question that surfaces in my mind on this sunny autumn morning, as I look out at these impressive oaks, is: what exactly took so long?

Druidism today has often been stereotyped and pigeon-holed, dismissed as the hobby-like fantasy of eccentrics. But what was passed on orally from teacher to student at the time of the druids is a still living and accessible spiritual reality. As a worthy guide, the druid was able to put aside fear and show his or her being to the student in complete openness. Such a radical act of bravery contained within it the possibility of inducing a sudden gap in the student’s usual way of thinking, a “thin place” in the mind, where the Spirit suddenly coughs and interrupts the thinking process. The result is a glimpse of the sublime knowledge that is true knowing. It is the knowledge of life and death set against the backdrop of an invincible light within, potentially catalyzing a radical change of mindset, even of vocabulary. This wisdom is the basis of society and traditions in the East, but Buddhist monks were already visitors to pre-Christian Celtic Europe, just as the druids and Celtic peoples are known to have journeyed at least as far as Greece.

Zen Buddhist schools even today use riddles and stories (called koans) as devices to jar monks out of their usual dualistic thinking. One such riddle is called “The Oak Tree in the Garden”:

A monk asked Master Chao Chou, “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming to the West?” Chao Chou replied, “The oak tree in the garden.” The monk later asked the same question again, and Chao Chou replied with the same answer, adding with force, “Look at it!” The Celtic School of Buddhism is able to make use of this ancient oral tradition to teach the specifically druidic way of looking and seeing, making it possible to look past form to reality and to establish a non-dualistic interpretation of the world. To look in a new way is also to think about the world in a new way, and about the human being’s place in it. But this apparently new way of seeing is in fact an old forgotten way that was core to the spirituality of Celtic peoples, and to the wisdom held by the druids. Whilst they sought to share this with all, to know it personally requires the discipline of practice and the bravery of a warrior committed to the spiritual path. It requires the confrontational intimacy inherent in a correct teacher-student relationship. This takes time. Seeing the world from a place beyond the world, beyond transience, all beings are dralas. We can sally forth to meet them and work with them as “enlightened warriors,” or we can choose to remain ignorant, projecting our own shadow onto everything. But by patiently learning silence and looking deeply into the rhythm of nature, life and death need not hold us in the grip of fear, a trademark of the ego. In these modern mobile times, in which the descendants of Celtic clans have spread far and wide across the globe, the spirit of the oak tree remains accessible and unchanging, its roots reaching down into the soft fertile soil of our collective memory, the non-dualistic mind. This distinctively Celtic mind-stream, so loved by Chögyam Trungpa, continues to communicate to us from beyond the grave, and can – even today – take us beyond the fear of it.

The Celtic School of Buddhism is able to make use of this ancient oral tradition to teach the specifically druidic way of looking and seeing, making it possible to look past form to reality and to establish a non-dualistic interpretation of the world. To look in a new way is also to think about the world in a new way, and about the human being’s place in it. But this apparently new way of seeing is in fact an old forgotten way that was core to the spirituality of Celtic peoples, and to the wisdom held by the druids. Whilst they sought to share this with all, to know it personally requires the discipline of practice and the bravery of a warrior committed to the spiritual path. It requires the confrontational intimacy inherent in a correct teacher-student relationship. This takes time. Seeing the world from a place beyond the world, beyond transience, all beings are dralas. We can sally forth to meet them and work with them as “enlightened warriors,” or we can choose to remain ignorant, projecting our own shadow onto everything. But by patiently learning silence and looking deeply into the rhythm of nature, life and death need not hold us in the grip of fear, a trademark of the ego. In these modern mobile times, in which the descendants of Celtic clans have spread far and wide across the globe, the spirit of the oak tree remains accessible and unchanging, its roots reaching down into the soft fertile soil of our collective memory, the non-dualistic mind. This distinctively Celtic mind-stream, so loved by Chögyam Trungpa, continues to communicate to us from beyond the grave, and can – even today – take us beyond the fear of it.

To learn more about The Celtic School of Buddhism visit the Website and the Facebook page.