by Jude Neeme-Samson

For many years I have undertaken journeys to places that have touched my soul and spirit. When I was young in Southern Africa I walked up Mount Aux Sources, visited God’s Window and watched fish eagles on the waters of the Okavango swamp. They all remain within my memory and when I close my eyes and think of them I can cross time and space and enter their purity and purpose. Without even knowing it, long before entering the Druid path, I felt connection to sacred place and visited ancient beings and gathered blessings from star temples in my homeland.

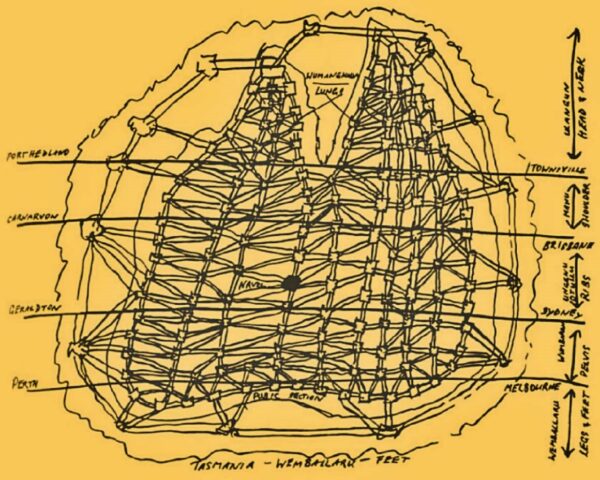

https://www.facebook.com/decolonialatlas/posts/bandaiyan-the-body-of-australia-by-the-late-ngarinyin-elder-david-mowaljarlai-ea/1189747804525622/

Here in Bandaiyan, the name given to The Body of Australia by the late Ngarinyin elder David Mowaljarlai, we live on a low laying island continent. The mountains of the Eastern ranges form two sequences of sacred peaks from north and south. Both meet at the most easterly point of the continent know as Mount Wollumbin (Mount Warning), the cloud catcher. The cloud catcher is the seventh mountain in both systems and is the place where the first drop of light touches our land each morning as the sun rises from the Pacific Ocean in the east. From the south, north-east of Naarm (Melbourne), where the rainbow serpent song line (Ley Line) passes by from Uluru and Kata Tjuta, the journey north begins at Mount Donna-Bu-Ang and follows north along the dividing range through Mount Bogong and Mount Kunama Namadgi (Snow Mountain), or Mount Kosciuszko, the highest point in the whole continent.

Mount Kunama Nanadgi is found heading south from Sydney through Canberra and up into the Snowy mountain highlands. This is on the left pelvis of her body. Mount Bogong is just a little further south and it is this landscape temple that creates the ecosystem for the experience of the temple of human frailty.

The Snow Mountain has many mysteries to it and the lessons of the Bogong moth stories form part of the understanding of living with frailty in the light of spirit. This temple is also close to the source of three rivers: the Thredbo (Snowy) River, which forms the foundation of the temple, the Murray and the Murrumbidgee rivers, which together form one of the lungs of the Murray-Darling river system.

To get here one can drive south from Canberra and snake ones way up to a town called Jindabyne and then either follow the river valley up to Thredbo or turn right and travel along the Porcupine ridge and land up at a small town called Perisher where a short walk takes you to the rocks that overlook both the valley and the mountainous highlands.

If you go up through the river valley you arrive in the village of Thredbo and after ascending via the ski lift there is a walkway to the summit. Along the way you cross over one of the creeks that feed the snowy river and if you veer right and follow the river and head up you find a flat open rock where you can lay down. It is here that you would be suspended between the earth and the stars above should you be able to spend the night here. It is also possible to recline there during the day and feel the stars in the sky during the day. The veils are very thin and vulnerable, and the whole place slows you down to listen to the song of the stars, the heartbeat of the mountain and the musical rhythms of the rivers. During winter these places are under snow drifts and cannot be easily accessed, however, in the summer months, short walks and hours of listening are available to reflect upon the frailty of being small within such a vast temple of earth and sky. At the same time one can feel the universality of human integration with the sun, moon, stars and earth. There is no separation.

Many sacred places have a focal point or structure to help the person seeking its guidance to find where and how to be present to its mysteries. The temple of human frailty is far more ephemeral and evanescent. The pilgrim searching to reflect upon their frailty and discover their inner strength for healing and spiritual presence needs to walk, listen and wander through the landscape. The lesson may come when a ripple of light on the brook next to the trail or a voice of a bird in the cold wind reaches your body. It is an open place where one has to slow down to the speed of nature or you may miss it, or even be caught up in the popular overlay of a ski resort or summer hiking destination.

This dreamtime songline that belongs here tells us of what engaging with vulnerability, curiosity and trusting our innate knowing of our direction in life can be. The Bogong Moth visits these highlands. Even though in recent years the city lights have distracted and disoriented the millions of moths that migrate over a thousand kilometres each year to get there, there is now a collaboration in the early southern spring months where cities are turning of all unnecessary lights in the evenings and, over the last two years, there is a slow return of the moths. Hopefully, a return that will bring them back from the brink of extinction. This is already a lesson in frailty. We are can learn, acknowledge and embrace that we are dependent on others to exist and flourish.

The migration of the Bogong moth is unusual as, besides surviving the heat, it appears to hold no reason for their life cycle. Each spring, they emerge from beneath the soil in Darling River plains up to 1,000 kilometres away, and navigate their way to the Alpine region. After spending the summer in the cooler mountain rock crevices and caves, they return to their birthplace to reproduce over winter. They become, as in all moth life cycles, new larvae again growing under the soil from plant roots and other plant matter.

During the summer the moths go into a state known as aestivation, which is like hibernation but during the hot and dry summer. The moths find cool caves and survive the summer in a state of dormancy. Then they fly the long journey home to lay their eggs. During the hot months the indigenous people came to the highlands and carried out cultural festivals and feast on the moths. The Moths’ summer sleep enabled communities to carry out important social interchange and cultural nurturing.

How do the moths know where to go? They don’t have an elder generation of moths to show them the way. The moths are night time travellers and have an internal compass that, along with external landmarks and star patterns, they find their way. It still remains a mystery how and when they choose to leave and travel such a vulnerable journey with many predators along the way. Is it because the heat of the plains would kill them? Whatever the reason they are the first identified migratory nocturnal insect to use this kind of navigation. Imagine the dangers of a journey where we don’t know the end point, the dangers on the way, the constructed dangers of the city lights that take them off their path and then sitting still waiting for the right time to continue the journey home. Many a metaphor for the vulnerability of our human life. The Bogong Moth also has an ultra-sonic inner ear that warns them of the dangers of predators like bats. What inner ear do we have that warns us of danger? How soft is this voice and how easily can we not take heed of its voice, or even miss its alarm?

In a dreamtime story Bogong Moth was once brightly coloured like our native wildflowers. Ignoring her husband’s advice, she went to explore the mysterious White Mountain in the distance. As she neared her destination, snow fell, trapping her. Spring came and as the snow thawed, Myee the Bogong Moth was released. Taking flight, her bright and vibrant colours remained, soaking into the snow and leaving her a dull brown. And where this snow melted, beautiful flowers emerged. This is a story of clarity of purpose against all odds and yet bringing something new into the world through offering parts of ourselves, sometimes without even knowing what that might be. New life born of the colours of our life.

The Bogong Moth, and any moth really, is a small very soft and vulnerable creature, frail and susceptible to damage. Yet, like Myee, we can learn to be aware of the advice around us and engage with our journeys with our own inner source of wisdom. What is right for you? What are the risks that might be unforeseen? Curiosity, the urge to explore and traverse new territory, and an open and inquiring mind, are all Moth qualities. Learn to be careful to focus on our ultimate goal, the distraction of an artificial light may not be easy to resist! Where in our life do we seem to keep on trying, unable to give up? Where are we striking out on a new journey, unknown territory and dangers for ourselves? We may change colour, leave our own mark through our adventures. The moth strikes against artificial light and seeks other natural answers to new dilemmas. As Myee the Bogong Moth journeyed new song lines, we can be prepared to take flight and explore unknown territory ourself! Following our heart has its risks. Or maybe you will unexpectedly change your colour, as our sister Bogong did. Or leave your mark – in many ways Bogong Moth is a symbol of artists as much as explorers. Life will certainly offer a challenge, will you accept?

The Bogong Moth, and any moth really, is a small very soft and vulnerable creature, frail and susceptible to damage. Yet, like Myee, we can learn to be aware of the advice around us and engage with our journeys with our own inner source of wisdom. What is right for you? What are the risks that might be unforeseen? Curiosity, the urge to explore and traverse new territory, and an open and inquiring mind, are all Moth qualities. Learn to be careful to focus on our ultimate goal, the distraction of an artificial light may not be easy to resist! Where in our life do we seem to keep on trying, unable to give up? Where are we striking out on a new journey, unknown territory and dangers for ourselves? We may change colour, leave our own mark through our adventures. The moth strikes against artificial light and seeks other natural answers to new dilemmas. As Myee the Bogong Moth journeyed new song lines, we can be prepared to take flight and explore unknown territory ourself! Following our heart has its risks. Or maybe you will unexpectedly change your colour, as our sister Bogong did. Or leave your mark – in many ways Bogong Moth is a symbol of artists as much as explorers. Life will certainly offer a challenge, will you accept?

The Temple of Human Frailty is a place, it is also open and variable. In many ways it is the landscape of our own journey and the courage to undertake it through inner knowledge that frailty, risk and new paths are all part of the temple we create through our frailty.