by Philip Carr-Gomm ~

I want to share a little information with you about Lewis Spence, a Scottish writer and occultist who was a Presider of the Ancient Druid Order – the group out of which the Order of Bards, Ovates & Druids evolved. The following does not offer a biography, which can be found here on Wikipedia, but some insights into his character and way of life provided by a friend of his – Charles Cammell.

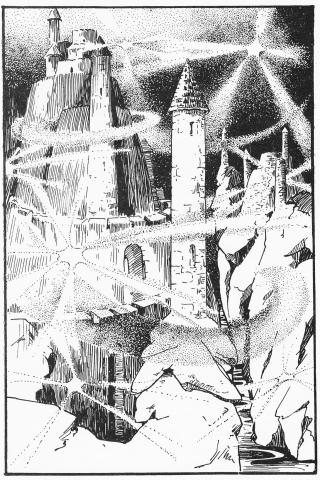

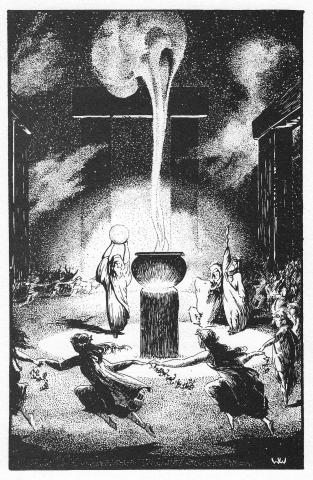

I first came across Lewis Spence’s work when I was studying Druidry with Nuinn (Ross Nichols). At that time I found a second-hand copy of his The Mysteries of Britain in a bookshop in Brighton and was captivated by his account of Druidry and by the pictures that accompanied the text – especially by the illustration of the towers of the magical city of the Druid alchemists at Dinas Emrys!

Only now, over forty years later, have I stumbled across a photograph of Spence (shown above) and some interesting biographical information in a book entitled Heart of Scotland by Charles Cammell, who was a fellow Presider of the Ancient Druid Order. He was also the Druid Ross Nichols chose to be the President of his newly formed Order of Bards Ovates & Druids in 1964.

When Cammell moved to Edinburgh in the 1930s he became fast friends with Spence, whom he describes thus:

‘Lewis Spence, as I first saw him…stands before me, clear in the eyes of my mind: a tall man, well built, inclined to corpulence. He is immaculately dressed (to the finest cloth and the best tailors he was ever loyal, and his suits always appeared to have been newly pressed). He is clean-shaven, his complexion fair and rosy, his nose Roman, his chin resolute. The eyes are blue, and rather small, with scant eyebrows. He is bald, but with fine, fair hair, greying, above the ears. His forehead is high and, as with most men of letters, slightly receding. His general appearance is that of a well-to-do professional man: a lawyer or physician: there is no trace of the Bohemian about him: one would judge his activities to be quite other than literary or imaginative. So I saw him – and still see him; nor can I as yet realize that he has left us: We shall go to him, but he shall not return to us.

At the time of our meeting – the spring of 1931 – Lewis Spence was at the height of a career of boundless intellectual energy and prodigious literary labour. In each of his many and divers roles he was active: his powerful and versatile mind moving almost simultaneously in the spheres of mythology, folk-lore, anthropology, history, drama, fiction, criticism, and poetry; to which was added intense political activity in the cause of Scottish Nationalism.’ [Charles Cammell, Heart of Scotland, Robert Hale 1956, p.27]

Just as it is today, the cause of Scottish Nationalism was riven by conflicting views, one group wanting complete separation and total independence from England, the other advocating a less radical split. Within each of these factions there was a further division – between monarchists and republicans. The monarchists themselves were divided between those who supported the British crown, and those who wanted a Scottish crown. Other fractures existed too: between Protestants and Catholics, socialists and communists. It was a mess, and after a while Spence grew weary of the constant disputes. He resigned from his position as Vice-President of the National Party of Scotland and concentrated on his writing.

Living in the 30’s in Arden Street in Edinburgh, and later at 34 Howard Place (Inverleith Row), by the Botanical Gardens (and which can be viewed in Google Street View) Spence married young and they had three daughters and one son. Each of his daughters acted as his secretary at some time. Cammell describes their family life – and indeed everything about Spence – in glowing terms, pointing to only one weakness: his concern for his health: ‘He was over nervous in matters of illness, or imagined illness, and in this it is likely that he was encouraged by the devotion of his family, always assiduous in their care for him.’ [Heart of Scotland, p.39]

Cammell explains that his friendship with Lewis Spence ‘gave direction to my study of Occult literature. Under his direction my understanding was enlarged. Thus it came about that we united in the publication of a magazine devoted to Atlantean and Arcane studies, and founded a publishing firm, The Poseidon Press. The first number of The Atlantis Quarterly appeared, under our joint editorship in June 1932′ [Heart of Scotland, p.205]. Cammell mentions ‘Among my own contributions to the Quarterly were my essays on Goethe and the Faust Legend and on The Magical Studies of Bulwer Lytton’, noting that his Faust essay could be found in Paul Christian’s History and Practice of Magic, edited by Ross Nichols [Forge Press 1952].

In 1941, when Cammell took over the editorship of the spiritualist magazine Light, he published contributions from Lewis Spence, as well as other occultists, including Montague Summers, Victor Neuburg and Dion Fortune.

That Spence was himself an occultist, and not simply an author of books on arcane subjects, can be seen from Cammell’s remark: ‘He was an initiate in an Order of international range and under distant authority, and from the personal evidence of his knowledge, which I was privileged to gain in our long friendshp, I can affirm emphatically its depth and unusual extent.’ [Heart of Scotland, p.30]

In Heart of Scotland Cammell offers us an explanation for Spence’s prodigious output that included over forty books, and puts those of us who are less organised to shame:

In Heart of Scotland Cammell offers us an explanation for Spence’s prodigious output that included over forty books, and puts those of us who are less organised to shame:

‘To the query, how was it possible for Lewis Spence to produce so vast a quantity of serious literature, to play a pioneer’s role in a national movement, both cultural and political, to preserve at the same time his liberty, and to enjoy no small amount of leisure? I answer with certainty that the secret of his power lay in his method – in the extraordinary discipline and orderliness of his mind and the methodical habits which his mind devised and imposed on his life and work. No man of thought or action could have lived and laboured with more exactitude of order than did Lewis Spence.

…Spence’s library, where he worked, was arranged always with the most minute precision. The desk was a model of tidiness: pens, paper, blotter, each in its place for immediate use; nothing used or useless lying about; not a book that he consulted while working, left afterwards out of its place on a particular shelf; the books, which numbered thousands, many of them rare and valuable, arranged according to subject and period. His work was arranged with the same orderly precision as his tools. Before commencing a book, he planned every part of it, every chapter or section of chapter, its matter, manner of treatment and length. He next marshalled his material, pigeon-holing the references required for each chapter in the order he had decided to use them. In this way he avoided all the difficulties which usually beset authors in the course of writing works of research; he worked with a minimum of fatigue, and almost without the wearisome labour of revision, and brought his work to its predetermined conclusion in an astonishingly short space of time.

Equally methodical was his use of time. His working hours kept time with his well-regulated watch. He started work at ten o’clock in the morning, and continued working until one, when he lunched: then, if the weather was fair, he took a walk; in bad weather he would read for pleasure some book unconnected with the subject on which he was engaged. After tea, he would write sometimes, but not regularly. His evenings he devoted to his family and friends, indulging his love of talk, or his love of music, for which he had a fine ear and unusual understanding: I remember that his taste was for French and Italian music, which he preferred to the German. He read books rapidly, extracting with almost uncanny accuracy and speed the material he sought. He read French, Italian, Spanish, Latin and German fluently and could talk pertinently on any subject and every theme of interest.’ [Heart of Scotland, p.35]

Cammell concludes this sketch of Spence’s work and play routine by noting its similarity with that other prolific writer and devotee of the occult, Bulwer Lytton. He is sensible enough to point out, however, that while they were both addicted to tobacco, ‘Bulwer’s addiction to laudanum was as far removed from Spence’s sober habits, as was Spence’s sedentary existence from Bulwer’s practice of vigorous physical exercise.’

The Scotsman published Charles Cammell’s tribute to his friend two days after his death.

LAMENT FOR LEWIS SPENCE

LAMENT FOR LEWIS SPENCE

3rd March 1955

Flowers are gay where still the snows are lying;

The woods will soon be green again with leaves;

And soon the happy swallows, homeward flying,

Will build their nests beneath the cotter’s eaves.

All lovely things return now with the springing

Of new life at the dawning of the year.

The bird, long silent, has resumed his singing:-

Why wails that Coronach? Why fell that tear?

A friend has gone, for whom there’s no returning:-

But we that mourn shall follow soon his flight.

Scotland, how large thy loss, reft of his learning!

Dunedin, thou art dark without his light!

Seek not his peer on Scottish moor or mountain:

Last of the Bards was he that lies at rest.

He drank deep from the Druids’ mystic fountain;

Then slept – and found the Island of the Blest.

~ Charles Richard Cammell

The Scotsman 7th March 1955

NOTES

For biographical details see the illustrated biography by George Knowles http://www.controverscial.com/Lewis%20Spence.htm

For the bare bones of his bio see the Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Spence